JAMES CARVILLE

A Warrior Tamed

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

June 1, 2002

WASHINGTON

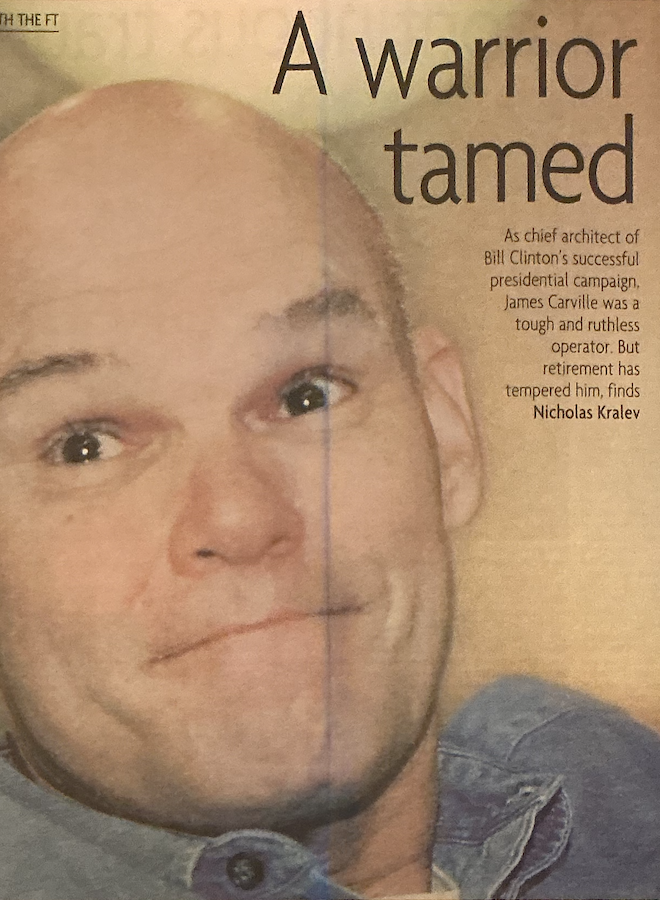

James Carville has officially retired from running U.S. political campaigns, but his retreat appears as much emotional and mental as pragmatic. Once an intense, tempered, tough and at times ruthless Democratic warrior, he is now an almost subdued family man who makes his living largely off his celebrity status.

Carville, chief architect of Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign, says it took him time to come to terms with the fact that his “day in the sun” had ended and now it’s “somebody else’s time”. He still misses “running campaigns, being in the headquarters and working with people”, but he didn’t even attempt to offer advice to Al Gore, the 2000 Democratic presidential candidate, or to Hillary Clinton’s senatorial campaign.

“My dirty little secret is that I like politicians,” says Carville, as he tries to explain his success as a political consultant. “They dare to fail publicly. If they mess up, it’s all over the front pages. What they do profoundly matters. When I was doing campaigns, one thing I knew when I went to bed at night was that I didn’t have an irrelevant job. I even accepted the fact that it didn’t matter who won the election.”

He is already sitting at the bar, a scotch on the rocks in hand, when I enter the West 24 restaurant close to Washington’s Georgetown neighbourhood, and instinctively turns around as I close the door. It’s easy to notice him from afar — he is tall and bold, and casually dressed in a red-blue shirt, blue jeans and sneakers, unlike most of the business-attired lunchtime clientele. In fact, he is not just a client, but also a co-owner of the restaurant, along with five investors, including his wife.

“We like to eat and it’s a lot of fun” to own such a place, he says, as we take our seats at a table for two in a quiet corner. The restaurant offers a menu inspired by the American South, with dishes such as roast pork loin with a hash of sweet potatoes. It has a soothing collection of French country landscapes on its dark yellow walls, as well as purplish dividers between some of the tables.

Half an hour earlier, at midday, I had listened to Carville on a public radio programme, where he was promoting his new book, “Buck Up, Suck Up and Come Back When You Foul Up”, which he co-wrote with Paul Begala, his professional partner of many years and a former Clinton White House adviser. The book, subtitled “12 Winning Secrets from the War Room”, is a practical reading on strategy — not only political — derived from the authors’ long campaigning experience.

Ownership has its perks: a waiter promptly turns up, ready to bring anything we want — from or outside the menu. Carville orders the “James salad” (definitely not on the menu) for both of us, without even telling me what it is, then roasted veal sausage for himself — he wants it “crisp” — and salmon filet for me (this time, my own choice).

Carville, who claimed that the “little boomlet of fame” he was beginning to encounter a decade ago wouldn’t go to his head, now says that “once you become famous, the only way you can make a living is by being famous”. As well as having written five books, he still does some consulting and gives speeches, for which he is reportedly paid about $25,000 each. And he’s no stranger to Hollywood — he had a small part in the 1996 Milos Forman film “The People vs Larry Flynt” and also appeared in the sitcoms “Mad About You” and “Spin City”.

His latest undertaking is co-hosting CNN’s daily political talk show “Crossfire” — a job his wife, the no-less-famous Republican strategist Mary Matalin, had until a year ago, except that she was “sitting on the right” and he is naturally “on the left”. At 57, he is still loud and passionate in his arguments, but some of the old fire he displayed whenever he appeared on television in the 1990s seems to have been quenched.

Carville and Matalin’s nine-year marriage, which has been called the oddest political union of the previous century, may have something to do with his transformation. “The thing about our marriage that surprises people most is how little politics comes up,” he says. “Our parents get sick and our children have needs that have to be attended to. So after we go through everything, who the hell has the energy to argue about politics?”

They first met in 1991, when Matalin, nine years his junior, was campaign director of then President George Bush’s re-election effort and arranged a meeting “to understand the strategies of the opposition”, after reading a newspaper article about him. Now they have two daughters, who are “not crazy about our notoriety”.

The “James salad” has arrived — it is basically a green salad with baby tomatoes and French dressing — and 15 minutes later the chef himself brings out the main course. Carville shows appreciation but quickly digs into his “crisp” sausage.

Having helped change an industry that had kept its political consultants hidden in back rooms, Carville burst onto the world stage several years ago, defying warnings that U.S. techniques wouldn’t work abroad, and advised candidates for high office in Israel, Britain, Greece, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador and Honduras. But he is not optimistic about his newest endeavour — for the region he wants to conquer next, the Arab world, presents a formidable obstacle: it doesn’t hold elections.

“If only they had an election in Egypt or other Arab countries, that would be great,” he says. “I’d love to go there. I get along well with Arabs. They are very passionate people like me, and I like to sit down with them and talk. But I know democracy and communications, so I won’t be very effective when there is only one-sided communication coming out.”

Another idea Carville has — more realistic, though no less challenging — is to visit Arab and Muslim countries on behalf of the U.S. government and do “some kind of propaganda” in the lands considered the cradle of terrorism, where anti-American feelings run deep. It may seem wishful thinking that George W. Bush’s Republican administration would entrust a star Democrat with such an important task, but Carville has serious White House connections: Matalin is now a senior aide to Bush and his vice-president, Dick Cheney.

“I’d love to use my experience and skills to tell people about my country and what’s available to them beyond hopelessness and terrorism,” he says. “What the terrorists are after is the younger and increasingly poor population. What they are offering is not that much, but we are not doing a good job telling those young people the other side of the story. It’s time we told them about choices they have without imposing American values.”

As he orders a glass of chardonnay for desert, he says he “didn’t start doing this for a living until my late 30s”. Born and raised in Carville, a Louisiana hamlet named after his family, he received a law degree from Louisiana State University, enrolled in the Marines, and was a high school teacher for several years. He then got a job at a law firm but hated it, and in the late 1970s began working on small, local campaigns. For a long time, success eluded him, but after a series of victories he was finally hired by Clinton’s national campaign.

A phrase Carville coined, “It’s the economy, stupid”, quickly became the campaign’s slogan and, before long, entered the political textbooks in the United States and abroad. Although he continued to advise Clinton after he assumed office, Carville never worked at the White House. According to some insiders at the time, he was marginalised because of his sharp language and inflammatory attacks against the opposition.

Carville, who accused the initiators of Clinton’s impeachment in the House of Representatives in 1999 of trying to overturn the results of two elections, has these descriptions of the two parties’ philosophies: “Republicans believe that if something is good for the powerful, it’s good for the country. Democrats think that if something is good for the people, it’s good for the country. So it does matter who is in the White House”.

“I have to go,” he suddenly interrupts himself as he stands up and gives me a handshake and a smile that makes his eyes close to slits. “But stay in touch with me.”