KEVIN COSTNER

Costner’s Last Stand

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

March 17, 2001

BURBANK

Kevin Costner has never given up on his search for the people who he reckons are the most “difficult to find”: the ones “who think outside the box”. He looked for them — futilely yet persistently — when he first called himself an actor and hoped that someone would hire an ambitious college graduate without a single acting credit on his CV. He broke just about every Hollywood rule when he produced, directed and starred in “Dances with Wolves”, the more than three-hour-long Western epic he had been repeatedly warned against, and it won him an Academy Award for best director, the respect of the filmmaking community and tens of millions of dollars.

He then defied all modern trends in his business, choosing non-commercial — and often unattractive by many standards — roles, some of which provoked harsh criticism and doubts about his talent. He has invested more than $20 million in businesses that haven’t made him a dime, and has been trying for years to build a luxurious resort in the Black Hills of South Dakota, against the will of the Sioux Indians.

Although those weren’t the most obvious choices someone else might have made, Costner believes they were the right ones. And along the way, he has found people who have stood by him and shared his passions and visions: fellow filmmakers, friends, relatives and, above all, audiences around the world. “People are good to me,” he says, “and it’s obviously because of the movies. They respect me and I try to respect them.”

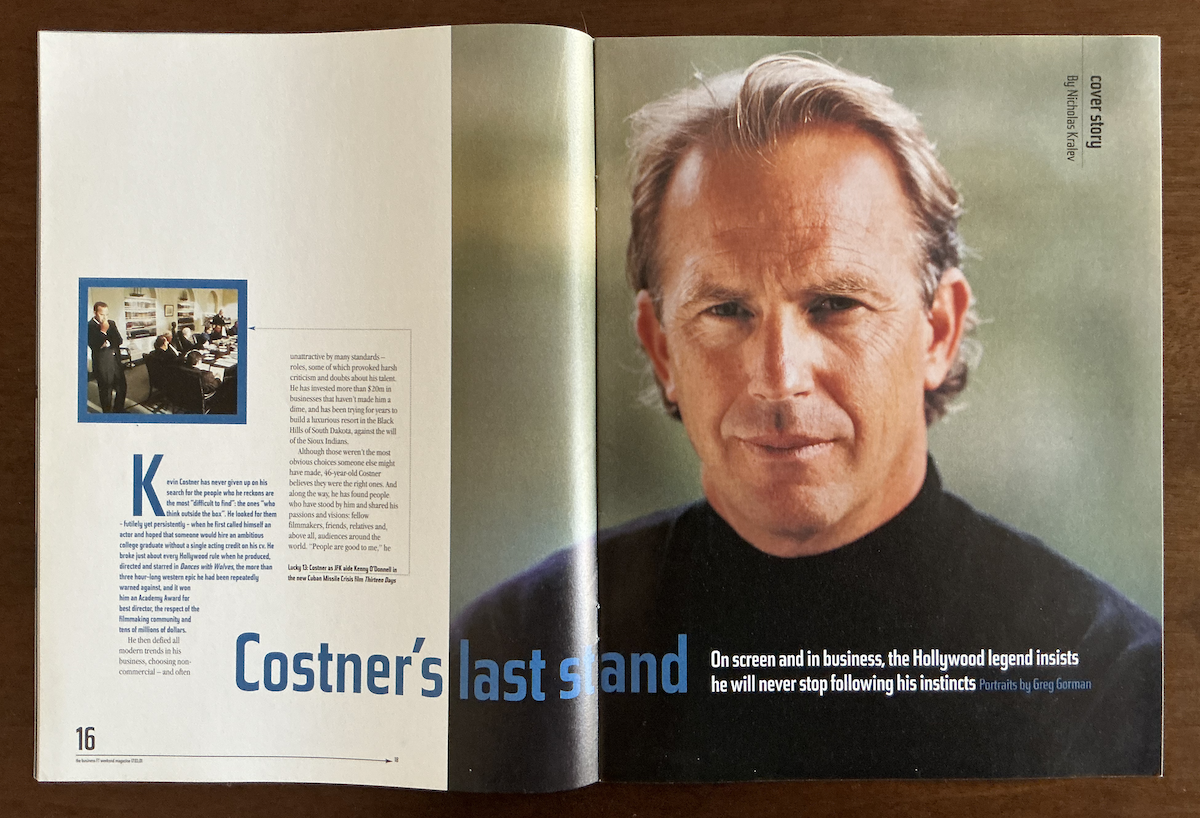

Costner has just embarked on the next chapter of his quest for “outside-the-box” thinkers with his new film “Thirteen Days”, a drama about the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, an event historians have called the closest the world has ever come to extinction. Instead of catering to demographics and making romantic comedies or special-effects action thrillers that are hits among teenagers, he picked a story that not only depicts intense policy deliberation and decision-making, rather than grandiose fighting, but whose unspectacular outcome is quite well-known.

“It’s important to see heroism and decisions that were not designed to keep you in office,” Costner says, referring to the way President John Kennedy and his brother, Bobby, handled the crisis. “It was a very good moment for them and for people to understand that it was this they are famous for, not Marilyn Monroe. I thought it was an important story in our history and the legacy of the world. It was a film I’d like to say I’ve made.”

Dusk has just fallen, and Costner is eating barbecue chicken on board his private plane. He suddenly pauses and tells me to turn around and look at the moon. It’s Sunday, March 11, and we are flying from Los Angeles to London (with a refuelling stop in Bangor, Maine), for this week’s British première of “Thirteen Days”. Roger Donaldson, the film’s director, and producer Armyan Bernstein are also on board.

“There are a lot of movies made in Hollywood, and they are usually about men fighting. This one is about men trying to avoid fighting,” says Bernstein, who is also chairman of Beacon Pictures and produced Costner’s 1999 film “For Love of the Game”, as well as such movies as “The Hurricane” (1999) with Denzel Washington and “Air Force One” (1997) with Harrison Ford. Bernstein says that, although “Thirteen Days” is about a time we like to think is over, “the unthinkable is still possible” — the United States and Russia still have nuclear warheads pointed at each other. It’s also a reminder, he adds, that no matter how capable a president’s advisers may be, decision-making is ultimately about leadership and can often be tough and lonely.

Donaldson, an Australian native whose directing credits include Costner’s 1987 spy thriller “No Way Out”, the 1988 Tom Cruise film “Cocktail” and “Dante’s Peak” (1997), with Pierce Brosnan, says “Thirteen Days” “exercised my skills at their maximum. It was the movie I’ve always been looking for; it justified coming to Hollywood”.

The film, which has had screenings at the White House, Congress and the United Nations, has enjoyed the overwhelming approval of the historians and Kennedy administration officials who were participants in what the movie describes. “We were very cautious about stepping far outside the events as they are essentially known to history,” the film’s other producer (with Bernstein and Costner), Peter Almond tells me. Costner, who plays Kennedy’s close aide and confidant Kenny O’Donnell, read the script during the 1997 holiday season and “responded in hours”, says Almond. “It was a great satisfaction to observe the filmmaking judgments and decisions Kevin made during production; he was fully engaged.”

Contrary to accusations that O’Donnell’s actual role in events has been blown out of proportion to fit Costner’s star power, the actor says his character was “scaled way back” from the original version of the script. “We didn’t want to make it like Kenny O’Donnell saved the world. That’s missing the point. I wanted to make sure that he wasn’t doing anything out of line. He wasn’t a person who sought the spotlight. There are a lot of people in public service who are very content not to blow their horn about what they did. Some of the most valuable men behind closed doors are the ones that in another room don’t speak up. They are very devoted to people and no one will ever know their true value. At the end of the day, we even say who he was: the friend.”

Costner knows something about those qualities himself. His friends describe him as a very loyal and serious man with integrity and responsibility. At the same time, “it’s important for him to have fun — he has an amazing sense of humour and is easy to hang out with”, says Tim Hoctor, a high-school friend of Costner’s who was reacquainted with him about seven years ago. Hoctor, who owns a real estate business in Ventura, California, hadn’t been included in the initial passenger list, but Costner called him three days before the trip and invited him to join the travelling party of six: “Kevin needed a friend to lean on”. “He’s a guy’s guy,” Hoctor says, “not a dreamy guy like Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt. He’s his own man. He has no secret agenda and nothing to hide.”

A right-to-the-point, no-nonsense person with a clear and quick mind, Costner has the confidence of someone who has learnt to appreciate everything he has achieved the hard way: by working and bleeding. Born on January 18, 1955, in Lynwood, California, he didn’t realise “we didn’t have a lot of money”. His father, Bill, worked for the local electric company and his mother, Sharon, was a housewife who later held a part-time job at an unemployment office. “Our vacations were camping trips on air mattresses — and now I’m flying my own jet,” he proudly looks around the cabin of his Gulfstream III, which has taken him to Europe, Asia and Australia.

Because his father’s job took the family to different towns almost every year, Kevin changed schools a dozen times. “I started to lose confidence in myself. I wanted the stability of going to one high school.” He also had to part with his dream of becoming a professional baseball player. “Since I wasn’t a pursued, recruited high-school athlete, I thought my career was over. The same thing started to happen when I took up acting [after graduating from California State University at Fullerton with a degree in business administration]. I’d never done a high school or college play, so what made me think I could be an actor? The old Kevin would have said, ‘You can’t be an actor, you need to have all those skills already in place.’ But the new Kevin said, ‘No, I’ll learn them. I know what I want to do and won’t have the fear of never getting there.’”

In addition, he didn’t have anyone in show business he could turn to for advice. “I didn’t even know you could become an actor; I thought those people were born on the screen.” And even though his mother hoped he would choose another profession, he knew he was “performance-oriented”: “When I played sports, I had theatricality about it. I understood the moments and the drama. When I went to movies, I laughed at great moments in films before the rest of the audience because I was right there with the character.”

But high art would have to wait — another seven years, as it turned out. Good thing he had always been a “worker”. He drove trucks, worked on fishing boats and in construction, and was a stage manager for three years. “I actually like manual labour. I don’t know how to work my computer — I don’t remember my password, so I have to ask my housekeeper.” He was paid $3.50 an hour as a stage manager and was happy to have the job. “It didn’t make for a very good conversation with my college chums, because they were getting their first or second house.”

His first acting parts were as “Frat Boy number 1” in “Night Shift” and “Man in alley” in “Frances”, both in 1982. Three years and seven films later came “Silverado” (1985), and in another two years the ball started rolling. The “Untouchables” (1987), “No Way Out” (1987), “Bull Durham” (1988) and “Field of Dreams” (1989) placed him among Hollywood’s leading men. He was ready for the series of risks he would take with “Dances with Wolves” (1990). “I put everything on the line,” he recalls. “It was said to be a movie that couldn’t be made, and we made it. We did tremendously well financially when all we were really trying to do was just make the movie.” The film made more than $500 million and won seven Oscars, including the awards for best film and best director.

Costner’s next decade of filmmaking saw some scathing reviews, unimpressive box-office performances, and even piercing personal attacks on his professional judgment. He says his intuition told him that he should do everything he did, but those decisions were based on deeply felt personal and professional values far removed from commercialism and bringing pleasure to the critics. So he did “JFK” (1991), the highly controversial Oliver Stone picture on Kennedy’s assassination; “The Bodyguard” (1992), where he co-starred with Whitney Houston; “Waterworld” (1995), which was declared a disaster but eventually grossed more than $400m, and “Tin Cup” (1996). He also directed his second movie, “The Postman” (1997), a post-apocalyptic thriller that failed commercially and critically.

Costner sees no need to regret his particular choices or the accusation that he makes long films because he likes to watch himself on the screen. “My style is lengthy,” he says. “The films I grew up on were ‘Spartacus’, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, ‘The Great Escape’ — all epic movies. I’d like to achieve commercial success just because it’s a nice thing, but it’s not a driving force for me. I’ve always been hooked on subplot, and those epics have them. My reputation for being difficult with studios is about those issues, not vanity.”

His other new movie is “3,000 Miles to Graceland”, where he plays a thief disguised as an Elvis impersonator, opposite Kurt Russell. He has just completed “Dragonfly”, which is expected to be released later this year, and says he’s contemplating three “period pieces”, one of which he might direct.

Following the financial success of “Dances with Wolves”, Costner became a target for many business people who approached him with different investment ideas. “If I was going to do something with money, it would be something that interested me, so I could pay attention to it,” he says. “So I got a think-tank of scientists and engineers about six years ago, with the idea of going after technologies that concern the environment. I’m not very good at talking about the environment; I’m more like a worker bee. If something terrible is happening, I like to fix it.” Costner set up two companies: U.S. Flywheel Systems, which is trying to come up with technology to store power, and Cinc, a centrifuge system that separates oil from water. “I put in more than $22 million and haven’t made a dime yet with the Flywheel, and I’m pretty close to breaking even with the other one. Most people will never stick with things as long as I have. I’m not driven by money, though if these things work, I’ll have even more money.”

He’s also hoping to have his resort in South Dakota built soon. He and his brother, Dan, bought the 85-acre property in 1992, but the project has stalled because of disputes with the Native American community and the need for additional investments. The resort, Costner says, will “prevent us from losing our legacy. I believe that the westward expansion, while it’s what we are known for around the world, was a heavy price paid by the native population. The hotel isn’t going to be a history lesson. It’ll be a place you enjoy, but everybody in the world who wants to understand where the American West is — and the most sophisticated traveller can’t even point you to it — I’d like that spot to have a real reverence to the people that were there before.

“Do you want to see something really cool, man?” he asks suddenly. “I’ll show you how backward I am. Four years ago I commissioned a sculpture for the hotel — the second-largest bronze in the world — 13 buffalo and three riders, riding these buffalo over a cliff to their death. If the hotel doesn’t go up soon, we’ll have to find a place to put it, because people should see it. It’s fantastic work.”

For his own rest and seclusion, Costner has a 35-acre retreat in Aspen, Colorado, where he spent a big part of last summer with children Ann, 16, Lilly, 14, and Joe, 12. He can talk about them for hours. “My children validate me,” he says. “I’m really proud of them. I tell them I love them and they are special every day. But I also tell them that they are no better than anybody else. I try to teach them how to think, not what to think. If you don’t talk to them, you lose your relationship with them, and it’s your job to do it. I know the one thing I’m good at in my life are my kids.”

The children spend every other week with their father, since Costner and his former wife, Cindy Silva, have had joint custody since their divorce six years ago. They had met in college, wedded in 1978, and their marriage lasted 16 years.

After years of rumour, gossip and speculation in the media, Costner was finally ready for a new relationship in 1999. “I didn’t for six years show up at the Oscars with someone on my arm,” he says. “My aim has never been having a casual girlfriend. Either have one or not. I have a responsibility to my daughters, so if I’m going to have a woman around, I need her to be a really good example. I was around good women, but for whatever reason it didn’t make sense to me, so rather than keep those things going until they didn’t work, I went without. It’s painful to break up, but it seemed the right thing to do.”

He says Christine Baumgartner, his 27-year-old girlfriend, is “a good fit, morally and ethically”, for him. “She is a really good woman; she has her wits about her. Her outside beauty is obvious. This is my first year of dating, so let’s not make too much of that. Let’s give this a chance.

“I’ve never been afraid to be in love again; I’m just terrified to be divorced again. I don’t want to go through that, because it’s of such international interest. I’d tell anybody to never give up on love. It’s the most powerful thing in the universe.”