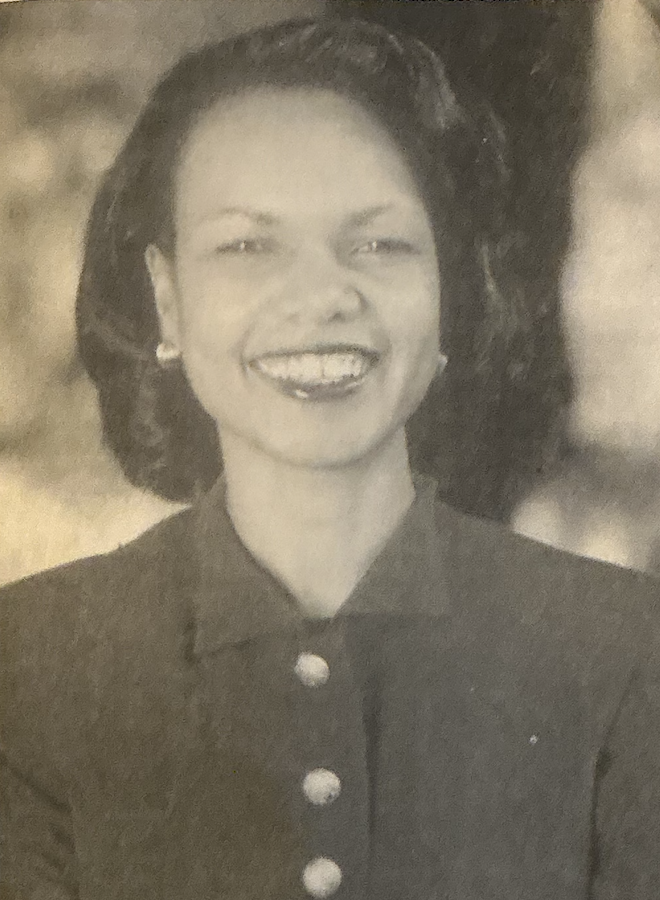

CONDOLEEZZA RICE

Political Punch in a Package of Charm

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

February 26, 2000

PALO ALTO

Condoleezza Rice has rarely heard a question she doesn’t know how to answer — from queries about her tumultuous childhood in segregated Alabama to her success in the male world of superpower politics, nuclear weapons and arms control.

She meets me with the friendly smile and easy hospitality of a West-coaster, defying the image of someone anointed by Washington insiders to become the most powerful woman in the world in a year. The chief foreign policy adviser to Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush, Rice is being tipped as a likely secretary of state or national security adviser should Bush win the White House.

As huge a task as this sounds, Rice’s own life story has the word “amazing” written all over it. At 45, she has been the first black woman in just about any job she’s taken on: from special assistant for national security affairs to President George Bush when she was only 34, to provost of California’s Stanford University, where she managed a budget of nearly $2 billion.

As we wait to be seated, I register her stylish dark-green suit and black polo shirt, and suggest that to call her achievements incredible is to risk being condescending. Rice, known to all as Condi, is used to such a reaction; she calls it the “Condi in Wonderland” phenomenon.

“I have a friend whose words for it are: ‘My goodness, the monkey can read! It’s amazing!’” she laughs, as we are escorted to our table. “I’m a package,” she says in a relaxed manner. “I’m 5-foot-8, black and female. I can’t go back and repackage myself. I can’t do an experiment to figure out whether any of this would have happened to me had I been white and male, or white and female, or black and male. So I spend no time worrying about it.”

We help ourselves to continental breakfast. “I always have a bagel or cereal for breakfast. Isn’t that boring?” she says. We are in Palo Alto, a small town 40 miles south of San Francisco and home to Stanford, where Rice is a professor of political science and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative think-tank.

Before meeting her, I had talked to Philip Zelikow, Rice’s former White House colleague with whom she co-authored what many experts call the best account of German unification, “Germany Unified and Europe Transformed”. He dismissed the notion that some of Rice’s jobs might have been the result of affirmative action. “Those jobs were too big and important to be just given out.”

At 26, she became a Stanford professor and the favourite of many students — her classes were often oversubscribed. She also won two of the university’s highest teaching honours. Her academic work on the Soviet Union and its military landed her a job at the Pentagon in the mid-1980s. In 1989, she moved to the White House as director of Soviet and East European affairs in the National Security Council.

The two “withering” years Rice spent as part of Bush’s national security team were probably the most dramatic and significant for American foreign policy in decades. The Cold War ended, Germany unified, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the United States and its allies won a war in the Gulf.

“It was an exciting time,” says Rice. “You could go to bed one night and wake up with some country having changed its social system overnight, with a new democracy to deal with.”

She first met Mikhail Gorbachev aboard a storm-tossed ship during his 1989 Mediterranean summit with Bush. “It was initially hard for the Russians to accept me,” Rice recalls. “I never figured out whether it was because I was female, or black, or young. But by and large, they’ve managed to deal with it.”

Her love for Russia — she speaks the language fluently — dates back long before her trips to Moscow as a White House official. “There is something about certain cultures that you just take to,” she says. “It’s like love — you can’t explain why you fall in love. Culture is something you can adopt, and I have a great affinity for Russia. It certainly has nothing to do with my ethnic heritage.”

Rice was born in the extremely segregated Birmingham, Alabama, of the 1950s. She wasn’t even 10 when the town became the epicentre of the civil rights movement in 1963. “It was a very tough and violent year and there were a lot of days we didn’t go to school,” she says. In spite of the turbulent times, “the community bound together to make certain that opportunities were given to the kids”.

Education was always a top priority in her family. Her father was a college administrator, her mother a schoolteacher. Her aunt has a PhD in Victorian literature. “So I should have turned out the way I did,” she remarks proudly.

In 1968, the family moved to Denver. In her Roman Catholic high school, young Condi, who had never had a white classmate before, was one of only three black students. As for her religion, she says she is a deeply religious evangelical Presbyterian.

She started college at the University of Denver at 15 — three years earlier than the typical American student. She went through English literature and American politics in search of a field to major in. A class she took in international affairs solved her problem.

She adored her professor, Josef Korbel, a former Czechoslovak diplomat who had fled both Nazism and communism and moved to the United States in 1948. Korbel took a personal interest in her. “He was a very engaging person, a great storyteller.” Having spent decades in his country’s diplomatic service, he gave her a rare perspective on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Korbel’s daughter, 17 years Rice’s senior, is Madeleine Albright, also a Soviet specialist. Korbel died too early, in 1977, to see his two students make history — his daughter as the first woman secretary of state; Rice’s rise to power has just begun.

Although Korbel taught both women the same lessons, they obviously drew different political conclusions, one becoming a Democrat, the other a Republican. “I know and like Madeleine very much,” Rice says. “You can have the same intellectual father and different outcomes, but there are some powerful core values that we share. On issues of how you use power we probably don’t agree.”

Rice thinks the biggest mistake of the present U.S. policy towards Russia is that “we got so wrapped up in Russian domestic politics — we had a script of how things were going, and it was actually very far from the reality. We called reformers people who were robbing the country blind.

“Let’s get out of Russian domestic politics. Let’s recognise the good things that are happening in Russia — free elections, more or less free press — and let’s get back to the state-to-state, great-power relationship in which we deal with the issues.”

It’s easy to recognise Rice’s philosophy and thinking in Texas Governor George W. Bush’s approach to foreign affairs. As head of his foreign policy team, nicknamed the Vulcans, she is in constant touch with him. Rice says of Bush: “I’ve never wanted somebody to be president so much. And it has nothing to do with me and my role, but with what he can do for the country.”

Although she says she’s “always taken life one step at a time”, all her career moves seem to be leading to a prominent job — perhaps all the way to president. She doesn’t think her career has hampered her personal life.

“I’m not married, but I never met anybody I wanted to live with,” she says. “I think I’ve maintained balance in my life. I’m not a workaholic; I’m pretty relaxed about things. I went back to playing the piano seriously four years ago. I exercise a lot and go to sporting events.” She is a big sports fan and once dated a professional football player.

She now spends much of her free time with her father, who moved to California after her mother died of cancer in 1985. She still remembers her parents’ words of encouragement in Alabama, when she was a girl.

“I lived in a place where you couldn’t go have a hamburger at a restaurant, but my parents were telling me I could be president.”

As I hear “hamburger”, I look at her bagel — it’s untouched. “No problem,” she says, and gives me that smile again. “I had fun. And there is a big lunch later.”