CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR

You Can't Hurry Love

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

October 23, 1999

WASHINGTON

She lives in Notting Hill, he in Washington’s slightly bohemian equivalent, Adams Morgan. Their 14-month marriage has been a whirlwind of weekend rendezvous and trans-Atlantic phone calls. The world sees them on television, sometimes even sharing a split screen, more frequently than they see each other in person. But the prospect of their first child — due in early April — has already started to change the way they live. They have spent more time together over the past few months, and though the decision where the baby will be born is yet to be taken, they both realise that compromises will be inevitable.

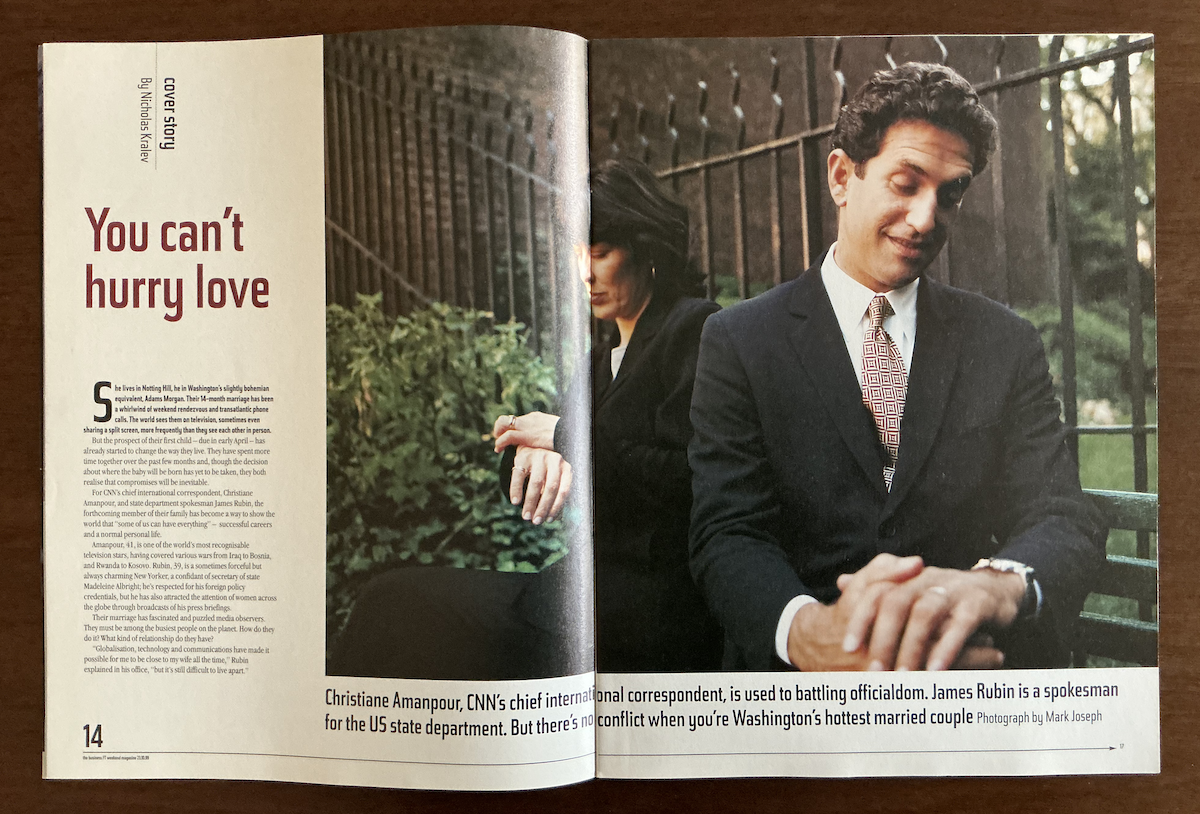

For CNN’s chief international correspondent, Christiane Amanpour, and State Department spokesman James Rubin, the forthcoming member of their family has become a way to show the world that “some of us can have everything” — successful careers and a normal personal life.

Amanpour, 41, is one of the world’s most recognisable television stars, having covered various wars from Iraq to Bosnia, and Rwanda to Kosovo. Rubin, 39, is a sometimes forceful but always charming New Yorker, a confidant of Secretary of State Madeleine Albright; he’s respected for his foreign policy credentials, but he has also attracted the attention of women across the globe through broadcasts of his press briefings.

Their marriage has fascinated and puzzled media observers. They must be among the busiest people on the planet. How do they do it? What kind of relationship do they have? “Globalisation, technology and communications have made it possible for me to be close to my wife all the time,” Rubin explained in his office. “But it’s still painfully difficult to live apart.” Even though Amanpour was in Washington that day, their evening plans had already been ruined. “I just learned I have to go to a White House meeting at 6 p.m.,” Rubin said, as he jumped in a limousine on its way to the U.S. Information Agency.

Sandy Berger, President Bill Clinton’s national security adviser, had called the meeting that morning after it became clear that the treaty banning all underground nuclear testing was poised for a defeat by the Senate. An arms-control expert, Rubin worked on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1996. Amanpour was hardly surprised by the evening’s disruption. In Rubin’s apartment later that day, she recalled a remark made by Iranian President Mohammad Khatami during a visit to Rome last year. He joked: “You see me more often than your husband.” “For the moment both of us realise that we have important jobs to do,” she continued. “We try to get together as much as possible, but we have to figure out how to live together.”

They try to see each other every two weeks. For the most part, she is the one visiting her husband, who, unlike her, has an office job. He flies to Europe “on formal holidays, on business, or if it’s really important”. The distance between them, and the fleeting time they spend together, are not their only concern. Ever since they announced their engagement in January 1998, Amanpour and Rubin have been battling accusations of conflict of interests, and even questions about their integrity.

It’s easy to see why. One of the world’s most famous foreign correspondents and the mouthpiece of American foreign policy often share CNN’s screen in times of international crises. She covers a conflict; he comments on it and offers the U.S. position. And though their territories don’t overlap, anti-U.S. foreign governments have accused Amanpour of being biased toward U.S. policies. To the surprise of some Washington reporters, at a briefing in January 1998, Rubin commented on an exclusive interview with President Khatami that Amanpour had just done. To suggestions that he should have restrained himself from discussing his wife’s work while speaking for the U.S. government, he replied: “I was responding to the answers, not the questions.”

Both Amanpour and Rubin strongly reject the conflict-of-interest accusation and insist that both of them had proved their integrity in handling delicate professional matters long before their relationship began. “I’d forged a very independent track record,” Amanpour said. “I’ve often been adversarial to what the U.S. government policies have been. Moreover, I don’t cover Washington, I don’t cover policy — I’m in the field, and I’m not in a position to be reporting any privileged information — it’s not part of my beat. Jamie’s job is to deal with journalists, not never to talk to the press. He knows what he can say and what he can’t.” Rubin has said the nature of their marriage is by no means an exception. “There are lawyers in Washington who work on [opposite sides of] the same cases. There are journalists who work for competing newspapers.”

Friends and colleagues of Amanpour and Rubin are unanimous that their marriage has changed both for the better. Their two-year romance has inspired numerous accounts of how besotted they are. “It’s all very natural,” said Nic Robertson, CNN’s London deputy bureau chief who, as Amanpour’s former producer, has worked with her more closely than anyone else. “They have great fun together.”

When Albright first learned about the relationship that would make headlines around the world, according to newspaper articles of the time, she chided her consigliere for “sleeping with the enemy”. “I can’t recall that,” Albright said. “But I was very happy that they had found their soulmate.” Tragedy prevented Albright from attending her spokesman’s wedding in Italy on August 8, 1998. Five hours after she arrived, on the day before the ceremony, the news of the bombing of two American embassies in Africa meant she had to fly back to Washington. The attacks on the embassies in Kenya and Tanzania left nearly 300 dead and more than 5,000 injured. “We were truly distraught. We thought we had to do something, but you only get married once,” Amanpour said. “It was almost inevitable that such a thing happened on our wedding. When people like us take vacation, our worst nightmare is that something should happen.”

Albright’s absence resulted in other dignitaries not turning up, among them Ted Turner, CNN’s founder, and his wife, Jane Fonda. But others, such as Richard Holbrooke, the new U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, as well as John F. Kennedy Jr. and wife Carolyn Bessette made it. Amanpour and Kennedy’s friendship dates back to their college days, nearly 20 years earlier, when they shared a house in Providence, Rhode Island. Last July, Amanpour and Rubin spent a weekend with the Kennedys at Martha’s Vineyard — the last for John and Carolyn, who died a week later in a plane crash off New Jersey.

How Amanpour and Rubin met was hardly idyllic. Amanpour covered Albright’s first trip to the war-ravaged Balkans as secretary of state in late May 1997, and Rubin was naturally on board. They were obviously not ignorant of each other’s existence — in fact, they had spoken on the phone in 1993. But it all started during that trip. “We were both smitten — in our own ways,” Amanpour said. Shortly after Christmas that year, Rubin proposed on a beach in Tobago.

Now the thought of parenthood makes them a bit nervous — as all first-time parents are. But in their case, it’s not just a question of juggling work and a baby, but of finding space to carve out a domestic routine in which a child can flourish. What happens when a journalist’s passion for the front line collides with a mother’s desire to stay with her child? “Motherhood is a very strange concept,” she said. “It’ll take me time to figure it out, because I never intended to have children — that wasn’t one of my goals. Everybody is saying it changes you radically, so I’ll wait and see. I’m trying to prove that some of us can have everything. It’s another part of the adventure.” Rubin, who had “a very close relationship” with his father, said he wants “to do the same thing”.

Asked how they would explain what they do for a living to their child when he or she is old enough to understand, they both took a moment to think. “I would say that I go around the world, turning the spotlight on bad people. I also try to explain to lots of people what’s happening in the world,” Amanpour said. Rubin’s answer was more laconic: “I’ll say that I speak for a great country and explain to the world why we are doing the things we are doing.”

Born into a wealthy Jewish family, Rubin discovered the ability “to talk to anyone about anything” at a very young age. “I didn’t hang out only with the nerdy, smart kids, but also with the sport jocks,” he said. His family thought he would to be a courtroom lawyer — he could argue for or against anything with equal zeal. He went to Columbia University in his native New York, where he received a degree in political science in 1982 and a master’s in international relations two years later.

“I was a junior in college when Ronald Reagan became president, and we incorrectly thought that he would blow up the world,” he said. His interest in nuclear weapons later became an obsession. “I wanted to learn everything I possibly could.” After graduation, he worked for four years at the Arms Control Association, a non-partisan Washington think-tank. In 1989, he joined the staff of the Senate Foreign Relation Committee and became foreign policy adviser to Senator Joseph Biden of Delaware.

Although Rubin and Albright met in the late 1980s, when she was at the Centre for National Policy, they had never worked together. But she didn’t think twice before she hired him as her senior adviser and spokesman shortly after Clinton nominated her to be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1993. “I hired him because he is very smart and loyal,” Albright said. “He is not only very knowledgeable, but understands how the issues are interconnected.” In addition to the “chemistry” between them, a real bond developed over Bosnia, Rubin said. “We were among a very small number of people who believed passionately in Bosnia” and tried to make a strong case for American involvement there. He dismissed speculations of a “mother-son” relationship with Albright as “excessive” imagination. “It’s true we are friends and very close, but she is my boss, after all.”

When Albright offered him the U.N. job, he said he would be “happy to work in sales,” as long as he could “also work in production”. Today, the ratio between sales (explaining and articulating policy) and production (policy-making) is about 60-40, while during the Kosovo war, for instance, it was 50-50. In addition to being the State Department’s chief spokesman, since the summer of 1997 he has been senior adviser to Albright and assistant secretary of state for public affairs. A widely recognised skill both Rubin and Albright share is their ability to produce effective soundbites. “It’s very important to be able to explain complicated issues in understandable ways,” he said over a chicken-sandwich lunch in his office at the State Department. But reporters’ tendency to use an explosive soundbite out of context has caused him serious trouble.

In December 1997, while describing the debate in Washington over whether to allow Iraq — under heavy U.N. sanctions — to buy more food and medicine with oil money, Rubin was pushed by a journalist to admit that the proposition was, in fact, “a carrot” for Saddam Hussein. Rubin walked straight into the trap. “It may be a little carrot,” he answered, “but there’s a big stick floating towards the Persian Gulf;” he was referring to an American aircraft carrier. Only the “little carrot” part of the quote hit the wires, with no mention of the “stick”. The comment was widely seen as a hint that Clinton was trying to negotiate with the Iraqi leader. Rubin has never been closer to losing his job. U.N.-based reporters who worked with Rubin there are not always flattering about the way he treated them, accusing him of being arrogant and cold. He admits he made mistakes, but insists things are now very different at the State Department.

In contrast to her husband’s smooth and inexorable rise, Amanpour’s success is more that of an American dream: an adventurous, small-town girl dreams of travelling around the globe and witnessing great events. And eventually she does. Born in London to a British mother and an Iranian father, she grew up in Iran. Although she went to school in Britain — Holy Cross Convent School in Buckinghamshire — she considered Iran her home until 1979, when the Islamic Republic was established. “My life changed upside down with the revolution. I was absolutely fascinated by the political events happening in my country that had such a profound effect on me, my family and friends. I was so interested in it, and I wanted to know everything about it, to observe it and report on it.”

She went to study journalism at the University of Rhode Island, and upon graduation was hired by a local TV station to do electronic graphics. In 1983, CNN — the world’s first 24-hour news channel — was in need of young, cheap talent. The people at the Providence station “encouraged me to apply to this new thing called CNN. They said ‘We hear foreign accents there.’ In September, CNN hired me over the phone. It was still very young and didn’t have many resources. For us, it was fantastic. You worked hard and moved up the ladder.” Then in 1990, CNN was looking for a correspondent in its Frankfurt bureau — a post no one wanted. That was Amanpour’s chance. “I had dreamed of going overseas. I didn’t have a particular desire to go there, but took it anyway. And I’ve never looked back.”

Amanpour has covered almost every big story of the decade. Her rare talent for delivering coherent live reports captured world attention during the Gulf War, but it was the Bosnian war that made her a star. Her reporting is often criticised for lacking objectivity. “Many people confuse journalistic objectivity with neutrality,” she said. “You can’t be neutral when genocide is being committed.” During a live satellite meeting with Clinton in 1994, she asked him: “Don’t you think your administration’s constant flip-flops on Bosnia set a bad precedent?” To which Clinton replied: “There have been no constant flip-flops, madam.” “It was hard and direct,” she said. “It was at a time when the so-called political reporters in the U.S. were asking him about his boxer shorts and his sex life. Those same reporters were apparently shocked that I had had the temerity to make the president so angry and to be so rude. I felt that I was doing simply my journalistic duty.”

She regrets that the age of the “grilling” in political interview is irrevocably over — in the United States, at least. “There didn’t used to be so much spin and public relations, and leaders actually spoke to reporters. Now it’s very difficult, because you can sit down with a leader, and you know they have been pre-briefed, post-briefed, side-briefed. The entire thing has an element of artificiality about it.”

Looking back to all she has achieved since she left Iran 20 years ago, Amanpour says she feels very lucky. Has she missed any chances? “How can you ask me that?” she says. “I’ve maximised every opportunity.” The answer to another question, however, has proved elusive: How to incorporate a baby into the routine of a couple who live for their work and are determined to live in the fast lane?

Being well paid certainly helps. Amanpour is reported to be making $2 million a year. Rubin’s salary is $118,000. But can money stop you from being torn between the professional duty that sends you off to war at a phone call’s notice and the child who wants you there at bedtime?

“Adding a baby is a massive logistical challenge,” Rubin said. “But we’ll have to overcome it.”