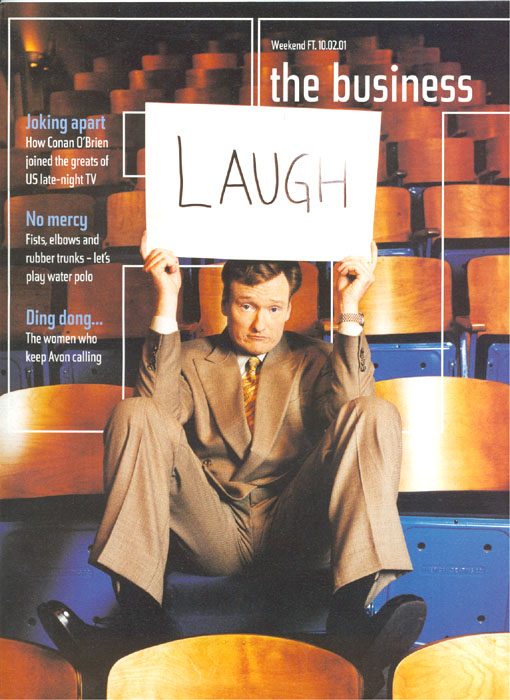

CONAN O'BRIEN

It's Show Time

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

February 10, 2001

NEW YORK

Conan O’Brien has no regrets that the longest election in U.S. history is over. True, Campaign 2000 and the 36 agonising days that followed were a gift from heaven for late-night TV hosts. They were courted by both Al Gore and George W. Bush, who made “nice-guy” appearances aimed at winning young voters, who are keener viewers of late comedy shows than the prime-time evening news. At the same time, they had a ball firing jokes at the candidates.

But now, with a new president in office, “it gets even better”, says O’Brien, beaming at the thought of the mocking monologues probably being born in the writing room of his show, “Late Night with Conan O’Brien”, as we speak. “Presidents get funnier all the time,” he says. “Nixon was a lot of fun for comedians — a good target. But Clinton may be the funniest. The bonus when you are finally president is that you don’t have to come on these dreadful shows anymore.”

As “Late Night”, along with other comedy programmes — such as “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” on NBC and “The Late Show with David Letterman” on CBS — makes media analysts ponder the impact they have on voters, late-night comedians feel on top of the world. Having had Democratic vice presidential candidate Joseph Lieberman sing Sinatra’s “My Way” on his NBC show, and made good use of all the negative points of White House contenders during the campaign, O’Brien says that his is “a good business to be in”.

The taping of “Late Night” has just ended, and we’ve swapped Studio 6A at NBC’s Rockefeller Centre headquarters in New York for O’Brien’s comfortable 9th-floor office. The 6ft 4in comedian has replaced his on-camera suit with jeans and a casual shirt and is kicking off the post-production part of his evening with a cold beer. I notice that he’s neither as lanky as he used to be — his reported $2 million salary has apparently made a difference — nor as carrot-topped as everybody describes him. “My hair is much more red on TV, from the lighting,” he agrees quickly. “It was never that red. It’s a misconception.”

Misconceptions are no novelty for O’Brien. Having watched him for an hour every night for seven years, millions of Americans have created an image of him based solely on “Late Night”. They expect him to joke and be funny all the time, and think that he’s kidding even when he’s serious. “Most people usually assume that I’m making a joke. When I try to complement someone sincerely, they think I’m being sarcastic. Sometimes I’d say, ‘You did a really nice job for me, thank you’, and they’d say, ‘Go to hell, how dare you, you are so mean’. And I’m just being nice.”

Another unpleasant consequence of having a job like his, he explains, is that, “when I walk in the street, since people see me only on the show, always smiling, they are not used to seeing me being just normal, and think that I’m depressed. I’m not — I just have this face, I’m neutral. I’m going to buy bread, or I’m walking my dog”. But he’s not, he’s quick to point out, one of those comedians who are “funny only during that hour they are on TV”, and “quiet and shy” in real life. “We always hear that Steve Martin, Woody Allen and others, who are really alive on camera, are introverted at other times. I don’t relate to that and don’t understand it. During the day, you’ll see me wandering in people’s offices, trying to make them laugh. I enjoy it.”

Most of O’Brien’s staff — about 60 people occupying the entire floor — are accustomed to his style. Some, however, never get used to the pressure of the daily deadlines and the speed, which often resembles that in a newsroom. “I have fired people who haven’t worked out,” he admits, “but not too many. I’ve had people murdered, but that’s a different story — it’s much easier.” That, of course, is a joke. And it’s a perfect illustration of how others’ expectations of O’Brien sometimes force him to play the funny guy from the show, rather than be himself. His jokes, however, aren’t always easy to distinguish from his “serious speak”. To make it easier for me, he suggests holding up his hand when he’s serious. But things work out without hand intervention, as soon as I engage him in a meaningful, intellectual conversation.

If one keeps him serious for a while, the 37-year-old O’Brien can be thoughtful and philosophical about his job. Although now everybody takes his success — and his refreshing yet nervous boyish charm — for granted, it took nearly four years to prove himself to network executives, audiences and critics. After many 13-week contracts and reviews calling his show “lifeless and messy”, he finally signed a five-year deal in 1997. But when he started, in 1993, he was virtually unknown, and many people accused him of not having earned his big break.

“After the first tough years, I felt I’d paid for that studio,” he muses. “I bled for this show. I put my heart into it.” He says that he realised he was “in a lot of trouble” at first, but never contemplated giving up. “In such cases, you tend not to think too much — you just do. There was no time to sit around and worry. If you are trapped in a burning house, you don’t sit on the floor thinking what to do. You start running around, try to find an open window and get out. What kept me going was that I really wanted it to work. Deep inside I knew I could do this. I just needed time to develop the skills.”

Confidence was the key to his “dramatic transformation”, O’Brien says. “I used to live or die by what I said every night. If I had something funny to say, I felt like a hero. But if I didn’t get a laugh, I was visibly unhappy and upset. It took confidence to realise that not everything I say is funny. I learned to enjoy the mistakes as much as the success. Now I make fun of myself for not getting a laugh.”

Today, with the wisdom of an almost veteran, he counters the notion that the way to succeed in a job like his is to learn how to play a TV talk show host. “That’s not true. The way to succeed is to somehow figure out how to be who you always were, but in a very strange environment — in a studio, with cameras looking at you. My struggle was finding a way to take this part of me that was very natural and spontaneous, get control of it and make it look the same in this artificial surrounding.” Unlike on “Friends” and “Frasier”, where an actor plays someone else for half an hour, “on my show, it’s me for an hour every night”. So, inevitably, “people are going to see who I really am. I can’t invent a personality, but I can showcase the personality I already have”.

Although he has always liked performing, as a child O’Brien never though that it would become his profession. “I was very serious, and I didn’t know that you could do comedy for a living — it was something you did with your friends. My hometown was as far removed from Hollywood as you can imagine. I’d never met anybody in show business — or any famous person for that matter.”

Born on April 18, 1963, in Brookline, Massachusetts (the Boston suburb known as John F. Kennedy’s birthplace), O’Brien was one of six children of a Irish Catholic family. His mother, Ruth, was a lawyer, and his father, Tom, a doctor, so Conan thought he’d do “something responsible”– “go to a good college, then law school, and then maybe get into politics”.

He followed his plan, but very briefly. He was a “smart student, with a good work ethic” and, after graduating from Brookline High School in 1981, he enrolled at Harvard, in neighbouring Cambridge. (“When I heard, as a boy, that there was Cambridge, England, I thought that they were copying us.”) He had written plays and sketches before and performed them for his friends, but it wasn’t until he started working for the Harvard Lampoon, the university’s venerable comedy magazine, that he realised that “adults were taking this seriously”. He decided that, if he could make $5 a day doing comedy, he’d go for it.

He eventually became the Lampoon’s editor — a position that helped him to get to know many of his fellow students. “Everybody assumes that only the smartest people in the world go to Harvard,” he says. “They don’t. It’s just a very unusual collection of people. A few years ago, when they caught the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, the news media were shocked that a Harvard graduate could be this weird, eccentric loner, who is bent on destroying society.’ I was the exact opposite: I said, ‘Of course he went to Harvard. I knew at least five future Unabombers when I was there.’”

Just before O’Brien left Harvard, the student newspaper asked him what he thought he’d be doing in 10 years. He said he’d have his own television show. He underestimated himself — eight years was all he needed.

He didn’t know exactly what he wanted to do after Harvard. He loved comedy and performing, but had no interest in acting. In 1985, he arrived in Los Angeles, where an acquaintance helped him to get a writing job on an HBO show called “Not Necessarily the News”. He also joined a local improv class — “Friends” star Lisa Kudrow was among his fellow students. Two years later, he began writing for the late-night series “The Wilton North Report”, but it had a short life, so O’Brien decided to move to New York. For three years from 1988, he worked as a writer for NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” (“SNL”). The show, featuring some of America’s top comedians, such as Phil Hartman, Mike Myers and Dana Carvey, helped him to make valuable professional connections. He appreciated the opportunity to create his own sketches, but when it came to performing, he was allowed only fleeting appearances as a crowd member or security guard.

In 1992, O’Brien joined the staff of Fox’s hit animated series, “The Simpsons”, starting as a writer and producer, and moving up to supervising producer the following year. But he wasn’t happy there, either. “As great as the show was, I was speaking through all those other established characters, while at “SNL” I could create a whole new world, with no limitations. Another frustration was that “The Simpsons” had a much more controlled environment, because it’s animation. You can spend a year on an episode to get it right. I loved the show, but it wasn’t mine — there is a big difference between being the manager of a Hilton hotel in Hawaii and running your own bed and breakfast.”

His B&B chance came sooner than he expected. In 1993, late-night legend Johnny Carson retired from “The Tonight Show”, and NBC sought a replacement. David Letterman, then hosting “Late Night”, was regarded as the heir apparent. The job, however, went to the little-known Jay Leno, and the deeply offended Letterman left the network, taking over “The Late Show” on CBS, which directly competes with Leno’s programme. The “Late Night” seat was now open, with no obvious front-runners. O’Brien begged executive producer and “SNL” creator Lorne Michaels to let him audition. He got the job immediately.

Having long been a fairly good writer but a “frustrated performer”, O’Brien had finally found the right combination. Although he would, for the most part, recite lines written by someone else, he could make a creative contribution at any time. But being in front of the camera made a world of difference. “When I wrote,” he recalls, “it was never over; I was always editing it in my head, torturing myself. Now, I can worry during rehearsals, but when the hour is over, the hour is over. It’s done, and there is another show to do tomorrow. It’s been good for me, because I needed to learn how to just let go of things — I’m obsessive and compulsive. I forget about what just happened and move to the next thing, and I do it as well as I can.”

With the initial scepticism forgotten, O’Brien’s show now attracts an estimated 2.5 million viewers a night. Although “The Tonight Show” remains NBC’s premier forum for Hollywood celebrities — and lately for politicians — “Late Night” has had luminaries like Harrison Ford, Sylvester Stallone, Elton John, Sigourney Weaver and Helen Hunt. “The booking is a nightmare,” O’Brien complains. “Fortunately, we’ve been around long enough to get good guests. At the beginning, it was very tough, because we had to make it funny with unknowns. But no show can survive if it requires Tom Cruise or Madonna — those people have to be a nice, occasional surprise.”

O’Brien says that he avoids watching comedy on television: “It’s like a dentist going home and cleaning someone’s teeth for fun”. He prefers documentaries and “serious movies”. He’s cautious about trying to learn from fellow comedians, afraid that doing so would take away his “unique flavour”. Unlike broadcast journalism, for example, where “you can learn certain techniques, comedy is a very personal thing”, he says. “Once you start to alter too much who you are, to reach some professional quality, you lose what many people tune in for.”

His own celebrity is now part of the reason for “Late Night’s” popularity. He thinks that “it’s fair game for the media to ask about my personal life — I have nothing to hide — but I’m not an important historical figure, so it’s good to keep some things private”. He has been single since his last, nine-year relationship ended in 1999, though the tabloids have been speculating about new girlfriends. “I’m going out with Cher now. Please write this!”

O’Brien returned to Harvard last June to give the traditional Class Day speech before the graduating class. “I was very much aware that someone else could have been speaking that day, and that no one might have remembered Conan O’Brien — a complete nonentity, who had graduated in 1985 with a degree in American history and literature and had vanished. That keeps me humble. I feel really lucky — I’m the poster boy for luck. Getting this job was an extremely fortunate break.”