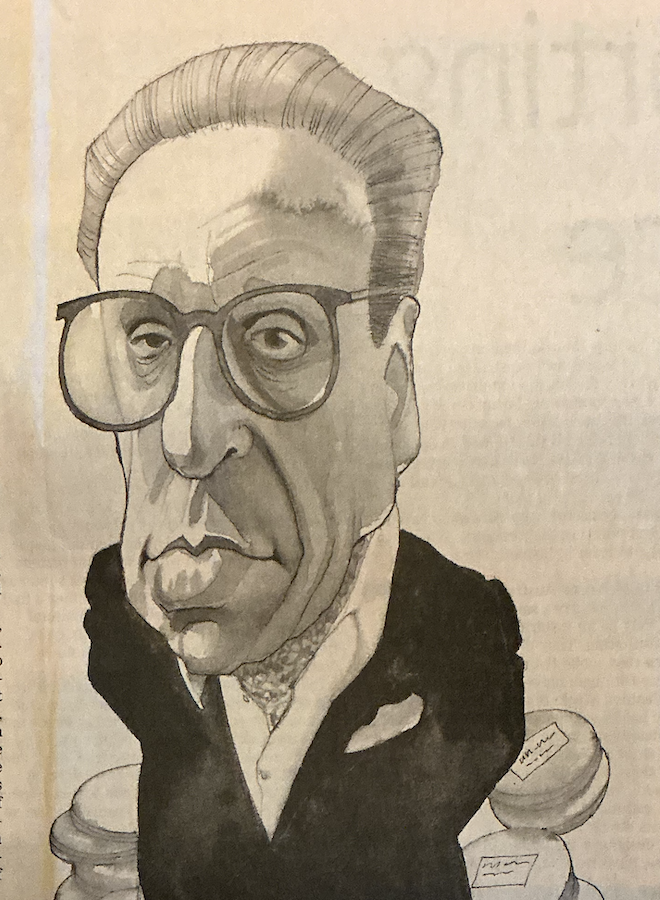

PETER BOGDANOVICH

Down So Long, It Looks Like Up

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

May 18, 2002

BEVERLY HILLS

Peter Bogdanovich is finally “up” again, but the warm reception his new film, “The Cat’s Meow”, has been getting is “strangely terrifying” to him. His first major movie, “The Last Picture Show”, which he made in 1971 when aged 32, was called the best work by a young American director since Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane”. After two more hits, however, his career nosedived.

“I’ve been down so long, it looks like up to me,” he says of the renewed interest in his work, although it couldn’t compare to the success he had 30 years ago. “It’s been a long time since I had a picture that the public liked, the critics tolerated, the studio backed and I thought it was the way I wanted it. That confluence of things doesn’t happen very often.”

“The Cat’s Meow” is Bogdanovich’s first feature film in nearly a decade, but he says it’s not “part of a grand comeback scheme”. He wasn’t even sure this was the right project after such a long silence. “I was a bit worried about doing a Hollywood story and what people would say, which is always a kiss of death, but luckily I got over my angst.” The absence of “out-of-control egos” of studio executives also helped. “I’m a well-known gun-fighter,” he says over a drink in Beverly Hills, where he is visiting from New York. “When I come into town, somebody wants to shoot me. This time there was no executive who wanted to show me how smart he was.”

Welles, with whom Bogdanovich became close in the 1960s, once told him a story about a mysterious death on newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst’s yacht in 1924. Even though the truth of what actually happened on board was never revealed, rumour had it that Hearst mistakenly shot pioneer filmmaker Thomas Ince, instead of Charlie Chaplin, whom he suspected of having an affair with his mistress, rising movie star Marion Davies. Fledgling gossip columnist Louella Parsons was said to have witnessed the incident, and had been awarded a lifetime contract with Hearst Newspapers in exchange for her silence. Welles had originally included a version of the story in “Citizen Kane”, but later took it out. He insisted that Kane and Hearst were two different people, despite the popular perception that his character was based on the mogul.

Bogdanovich didn’t look at the story as a potential movie idea until late 1999, when he took his first ocean voyage in 20 years. The cruise was also a film festival, and the critic Roger Ebert was on board, “deconstructing ‘Citizen Kane’ for the passengers”. The director told Ebert what he had heard from Welles three decades earlier, only to receive a spontaneous — and, as he soon realised, obvious — reaction: “It sounds like it will make a good movie”. By a peculiar coincidence, when Bogdanovich returned home, he found on his desk a script based on that same story, titled “California Curse”.

Because no one knows exactly what went on that November day, the director says he and writer Steven Peros, as well as the cast, did serious research on what is known and tried to be “faithful and honest to the characters“.

He says the casting “went strangely”, with “everybody making a contribution”. Twenty-year-old Kirsten Dunst, who plays Davies, “was suggested by the studio,” Lions Gate. Bogdanovich “couldn’t figure out how to cast the Chaplin part, which is always very difficult”, but when he saw British actor Eddie Izzard on the New York stage, 10 minutes was all he needed to make up his mind. “Eddie is not a stand-up comic — he’s an actor of comedy,” he says. Izzard, in turn, proposed a colleague from London, Joanna Lumley, for the part of eccentric Victorian novelist Elinor Glyn. For the role of Hearst, American Edward Herrmann “was a last-minute decision, although we thought of him earlier, but the studio felt that they wanted a bigger name”.

Bogdanovich, is a very hands-on director who considers the entire filmmaking process part of his job. “I don’t think it’s anybody else’s business where the camera goes except mine. Sometimes directors of photography make suggestions, but I rarely take them.” As for working with actors, he says he directs “by showing people what I mean” — unlike Robert Altman, for example, who leaves it to his actors to “figure out” how to play a character. “Some actors don’t like it, but they get used to it, because they understand that I don’t mean for them to imitate me, but to take an idea from me. If they are secure, they don’t mind it.”

His method may have something to do with the fact that, in his early years in the business, he frequently and notoriously hired young and inexperienced actresses for lead roles. Actor Cary Grant advised him not to fall in love with his leading ladies, but Bogdanovich didn’t listen. He began an affair with Cybill Shepherd while filming “The Last Picture Show”, a coming-of-age story set in a small Texas town, and turned her into a star. But their two later films together, the 1974 costume drama “Daisy Miller” and the 1975 musical “At Long Last Love”, were flops. In 1980, he met Dorothy Stratten, a Playboy Playmate, whom he cast in “They All Laughed”, with Audrey Hepburn. Eight years after Stratten was killed by her husband, who was jealous of her relationship with Bogdanovich, he married her younger sister and gave her a small part in “Noises Off”.

Today, he says that many people think these affairs hurt his work. In the case of “At Long Last Love”, “which was the most notorious, I screwed up, because the picture we finished was much better than the one that was released, but they blamed it all on Cybill. The irony was that years later she had a triumph in the TV series ‘Moonlighting’, playing basically the same character.”

Stratten’s murder before “They All Laughed” opened wasn’t the only time Bogdanovich had to release a film with a dead actor. In 1993, the 23-year-old star of “The Thing Called Love”, River Phoenix, died from a drug overdose. “I loved him dearly,” says the director. “He had a wonderful talent.”

Bogdanovich himself wanted to be an actor, and took acting classes in his native New York. He was participating in the American Shakespeare Festival one summer when he spontaneously decided to direct a scene with a group of fellow actors, because “I got to play all the parts on some level”. Throughout his youth, he took notes on every film he saw on blue cards, which — they number more than 5,000 — he now keeps in a storage room next to his bedroom.

Not only did he study meticulously the great figures of cinema’s early years, but he also knew many of them personally. In 1997, he published a best-selling book of 16 interviews called “Who the Devil Made It”, for which “I received the best reviews I’ve ever got”. Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford and Howard Hawks were among the featured directors, who “didn’t grow up wanting to become filmmakers — because there was no such profession then — so they did other things; they all had a life and knowledge of things outside of movies, while it seems that most of us grew up knowing only about show business”.

Bogdanovich’s career has been compared to Orson Welles’ for its early peak and subsequent downfall. Bogdanovich points out that “Citizen Kane” wasn’t a financial success when it came out, although it has been often proclaimed the best film of all time. In contrast, he says, “The Last Picture Show”, as well as his next two hits, the Barbra Streisand movie “What’s Up, Doc?” and “Paper Moon”, “made a lot of money”. But just as Welles “didn’t want to talk about ‘Citizen Kane’, because it was the only film everybody knew he made”, Bogdanovich doesn’t consider “The Last Picture Show” his best movie. “They All Laughed” gives “the best portrait of who I really am,” he says.

The films he is most reluctant to discuss are “Mask” (1985) and “Illegally Yours” (1988). The first “was as good a movie as I’ve made — Cher, who won the best actress award at Cannes, was very good in it — but suing Universal Pictures for cutting scenes was a mistake on my part. I was upset, because the movie I finished was very sad but not depressing. It was touching, even heart-breaking, but you didn’t come out of it depressed, as I thought you did with the version that was released, because they took out a lot of the joy.” As for “Illegally Yours”, with Rob Lowe, it was a “terrible movie and I only did it because I needed some money”.

The next picture Bogdanovich hopes to make is a “ghost film” called “Wait for Me”, about a bankrupt director who reflects on his life and career. Having declared himself bankrupt twice, Bogdanovich is now being careful not to slip into the spending spree of the 1970s.

“You never know in this business,” he muses. “It’s awful how insecure it is, and I haven’t had much financial security for a while, which is aggravating and somewhat debilitating.”