ANJELICA HUSTON

Must Be Talking to an Anjel

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

March 10, 2001

SANTA MONICA

Anjelica Huston has already come to terms with the fact that her first half-century will soon be behind her, but the prospect of joining the ranks of Hollywood’s much-pitied unemployed middle-aged actresses has yet to make her list of immediate concerns. With three films scheduled for release this year, another one having just started production and a script she’s writing to direct, Huston is now busier than she was in her early 30s.

She claims that one can “always find jobs” in show business, or “create jobs if one can’t find them”, although she says that her turning to writing and directing “certainly wasn’t as a result of not getting any work”. “Most young actors aren’t being offered parts, either, so what’s the point of harping on a negative when you can create something?” she demands. “Go to a class, learn to dance, do something with your life, but don’t sit complaining about what you haven’t got. I don’t have $100 million — it’s too bad. But I can go and figure something that will get me my next $10 million.”

An Academy Award winner, with three Oscar and seven Golden Globe nominations in her honours collection, Huston became a star in her own right, even when still in the shadow of her father, legendary director and actor John Huston, and Jack Nicholson, with whom she had a 17-year relationship (with three intermissions). She doesn’t mind the numerous questions she’s had to answer over the years about the two men, because they “were and are pertinent to my life — I should be grateful for being asked about them”. Today, the man in her life is Robert Graham, an award-winning sculptor, whom she married eight years ago. “It’s a good and solid relationship,” she says, “and we are good friends.”

Huston plans no “huge celebration” on July 8 — she says she gave up “lavish birthdays” when she was 28. Not that turning 50 is an insignificant event (“that’s grown-up; it’s OK to do what you want at 50”), but life goes on. “At first you are shocked to be at that age, and then you get over it and feel rejuvenated and youthful again. When you are young, you don’t have time for much. For some reason, the older you get, everything is shorter, but you seem to have more time to do things. You are not so impatient and easily bored.”

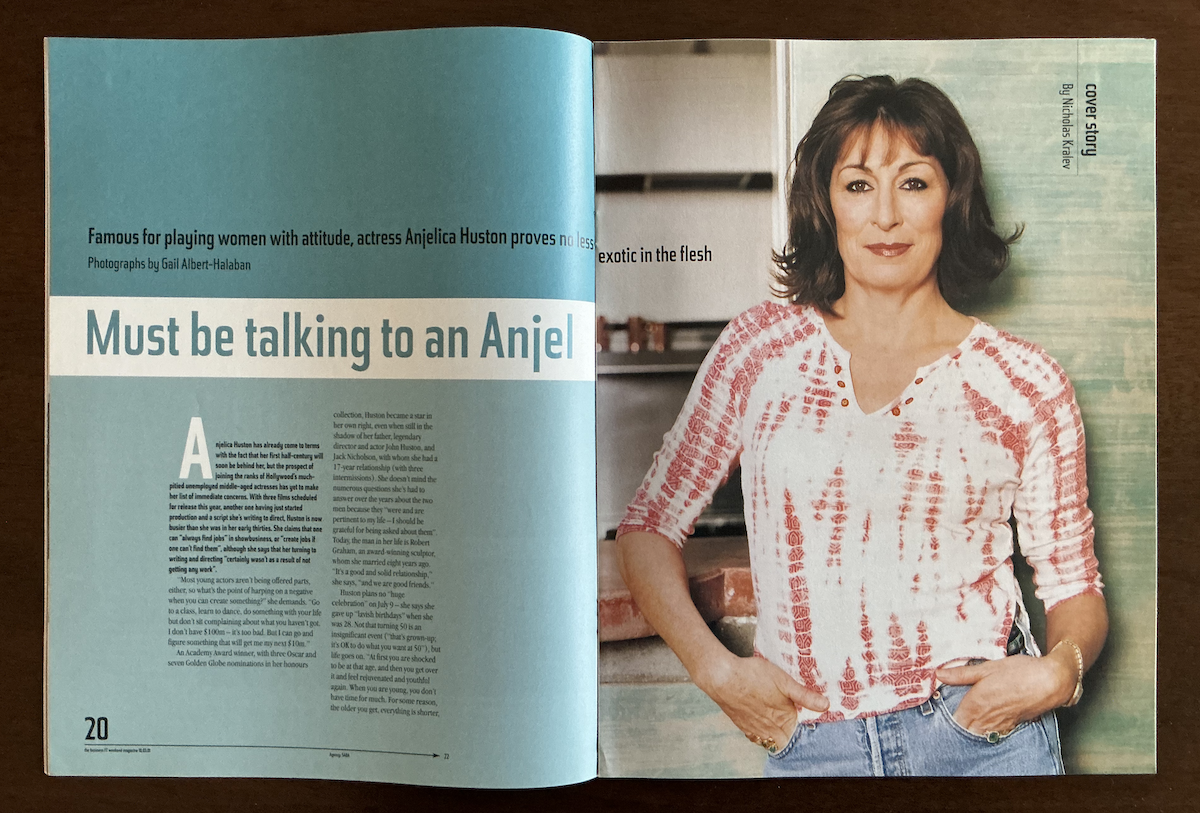

We meet in Santa Monica, California — Huston’s birthplace — at one of her favourite French restaurants, where we have a room of about 10 tables all to ourselves. Six feet tall, dressed in an elegant black suit, with dark-chestnut hair and vast brown eyes, she fits the descriptions of most of her on-screen characters: she is majestic, handsome, sleek and a little wary. The only obvious difference is that the arching of her phenomenal eyebrows in regular conversation is not nearly as frequent as that of her heroines. As we talk longer, another contrast becomes apparent: unlike the tough, often mysterious and sometimes evil women she has played, Huston is much more down-to-earth, polite and soft-spoken.

“I’ve actually played a few flesh-and-bone women,” she points out, referring to “Agnes Browne”, a widowed mother of seven in working-class Dublin, in the 1999 film of the same name, and the Holocaust survivor Tamara in “Enemies: A Love Story” (1989). “But playing Morticia Addams in ‘The Addams Family’ [1991] and Lilly Dillon in ‘The Grifters’ [1990] pretty much sews up the audience’s attention, so I’m not sure people are that crazy about seeing me as a good woman.”

Despite film critics’ concerns about her having been typecast early in her career, Huston has been entrusted with rather different — and usually difficult — parts. Her new roles follow a similar pattern. In “The Golden Bowl”, a James Ivory picture based on Henry James’s novel about a man who marries an heiress for her money but is actually in love with her friend, she plays opposite Nick Nolte and Uma Thurman. The TNT film “The Mists of Avalon” tells the story of the women behind King Arthur, with Huston as his aunt Viviane. In “The Man from Elysian Fields”, she is a wealthy woman who hires a failed novelist (Mick Jagger) for his escort service. And in “The Royal Tenenbaums”, a movie about the misadventures of a family of geniuses, she co-stars with Gene Hackman and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Huston is also adapting Dawn Powell’s 1942 book “Time to be Born” for a film she hopes to direct. “I’m starting to write more than I have for years,” she says. “I’ve always liked writing — I was drawn to it in school. I kept a diary, but at one point it was read by a friend and that stopped me writing for a while. But e-mail started me up again. I like it; it’s a great exercise, because it’s immediate and makes you think quickly.” She corresponds electronically with “friends, relatives and other actors”, but doesn’t surf the net unless she needs something specific. She says she’s never checked out the Anjelica Huston pages on the web and “wouldn’t dream of discussing myself in a chat room. I’m too easily hurt by what people say. It’s not constructive, and I take it personally”.

Neither does she get her news from the net, preferring instead “to touch” the newspaper in the morning. She says she follows the first steps of the new George W. Bush administration “with amusement” and is “hard-pressed to understand the climate in which our new president can turn back time”, a reference to the ban Bush imposed during his first week in office on the use of federal funds for aiding overseas organisations promoting abortion. “It’s medieval that we can be even discussing abortion at this point,” Huston says with asperity. “I find it really disturbing that America has voted this way — or so we have been led to believe.”

Coming from a family of Democrats, Huston has long supported the party — both morally and financially — and has a deep respect for Bill Clinton. She thinks he was a “very good president”, and probably would have been better “if he had been given the chance to operate unhindered by the constant attacks on his character”. Huston, who has met Clinton about a dozen times, describes him as a “wonderful, heartfelt, informed and conversational” man who “remembers your name across a room and the last time he saw you. He manages to make a crowd of 500 people intimate. He’s extraordinarily gifted and a great humanitarian”.

She maintains that there was “a real change under Clinton” in the United States and, at the risk of sounding “incredibly self-serving”, tells me she quit smoking as a result of his administration’s anti-tobacco policies. “I was a big smoker when Clinton came to the White House in 1992, and after the first four years the whole smoking thing that went on in Washington irritated me. All of a sudden it became a national thing — you couldn’t smoke in a restaurant, in the park, in the open air. But he really influenced people, and if you look at the numbers, you’ll see a big difference. That was a positive, helpful and clever thing, even though those of us who were avid tobacco consumers were very irritable. But it really came home. I gave up smoking, and that was a very healthy thing. It was a healthy presidency.”

Huston says she would gladly support Hillary Clinton if she decided to run for president in 2004 or later. “I’d vote for Hillary — sure I would. I’d like to see a woman achieve the presidency in my lifetime.” She feels comfortable living away from Washington politics, although she cares about her community and the people around her. She is appalled, for example, that California’s beaches are “full of garbage” — she’s gone down the beach between the Venice and Santa Monica piers “picking up straws, just to see how many you can possibly collect”. She finds the people in Los Angeles “ruder” and tempers “shorter”.

“People are much more ambitious than when I was first here. We were much more laisser-faire and not quite so self-promoting. We used to make our own decision what to wear and where to go, and it wasn’t a live-or-die thing whether you showed up at the Golden Globes or not. You had to show up for the Academy Awards out of respect for the Academy. But it wasn’t necessary for everyone to thank everybody they knew. It was an opportunity for people to say something different. I miss those days. Everything has become so safe and tame. You can’t tell whether someone has a good or bad taste anymore, because they are all dressed by designers and are wearing somebody else’s jewellery. I don’t want to be sour grapes, but insincerity seems to be ruling these days in Hollywood, claptrap and nonsense. There is a blueprint of how you behave, and regimented things cut out the fun.”

Although many have argued that artificiality and shallowness are nothing new to Hollywood, it was indeed a very different time when Huston was inducted into show business, where her family roots run three generations deep. As well as her father, her grandfather, Walter Huston, was a famed actor and a favourite of former President Franklin Roosevelt (“He used to have dinner in the White House kitchen with Eleanor and the president; they were tight friends”). Walter won an Oscar in 1948 for “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”, and his son John, walked away that same night with the Best Director award for the same film. Thirty-seven years later, John Huston directed his daughter to her own Academy Award.

He was filming “The African Queen” in the Belgian Congo in the summer of 1951, when he received a letter from his wife: “You have a daughter. Her name is Anjelica, with a ‘J’”. After spending the first decade of her life at St Clerans, a 150-acre estate in Ireland’s county Galway, Anjelica moved to London with her mother, Ricki Soma, a New York ballet dancer who, at 20, had become John Huston’s fourth wife, but died in a car accident in 1969.

When Anjelica was 17, her father decided to launch her acting career with a role in his film “A Walk with Love and Death”, a lyrical tale about a young man in war-torn medieval France. The movie was a disaster, which made it even harder to swallow for Anjelica, who had disliked the script from the beginning. She was longing to play Juliet and was on a school search for Franco Zeffirelli’s film “Romeo and Juliet”. Now she thinks that episode was “one of life’s little hiccups”.

In 1971, a friend of her mother asked Anjelica to model for a Vogue fashion shoot in Ireland. That offer kicked off her short but successful modelling career, which brought her back to the United States. In 1973, she met Jack Nicholson at a party in his house. Their stormy relationship ended in 1990, when Anjelica learned that Jack was having a child with actress Rebecca Broussard. Huston finds it none of her business to opine about Nicholson’s latest relationship, with the 30-year-old TV and film star Lara Flynn Boyle, 33 years his junior. “I like and see him, and we have a nice relationship, but I don’t spend my time thinking about his girlfriends.”

For about a decade after arriving in Hollywood, Huston had small roles in films such as “The Last Tycoon” (1976) and “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1981). Then, in 1985, came mafia princess Maerose Prizzi in “Prizzi’s Honour”, the part that made her a star — in the eyes of others, if not in her own — and won her an Oscar. Her father directed her again two years later, in “The Dead”, James Joyce’s story about a young man’s jealousy of his wife’s dead lover. It was John Huston’s last film.

Anjelica learned her craft not only from her father, but also from Peggy Feury, a legendary LA acting coach who was among the few people Huston thanked in her Oscar acceptance speech. She still remembers one of her first classes when Feury gave her an “ambiguous” piece about a woman dealing with a man in a room. The man could have been anyone — son, husband or father — and Huston’s job was to “be specific in an ambiguous situation”. At one point, the part required that she ask that man for something, so she put out her hand. After the scene was over, Feury said: “Anjelica, you are big and arresting — we pay attention to you. If you are asking for something, we’ll give it to you. You don’t have to put out your hand.” “She deemphasised me as an actress and relaxed me,” Huston recalls. “That took the stridency out of my performance.”

In spite of her Oscar, the Academy Award nominations for “The Grifters” and “Enemies: A Love Story”, and the high critical acclaim she received for her subsequent roles in “Crimes and Misdemeanours” (1989), “The Witches” (1990) and “Manhattan Murder Mystery” (1993), Huston never felt like she “made it” as an actress. “Every time I complete a job, I feel a sense of satisfaction,” she says, “but I move on to the next one. You have to be constantly reinventing yourself — you can’t rely on the last job you did. I was having dinner with Sir Peter Hall the other night, and he was telling me about Laurence Olivier. He would shake before he went on stage and had to be pushed on. Someone who thinks they will never make it — this is what makes an actor.”

In 1995, Huston took up directing, which she regards as “a good way to learn about your own instincts”. Her first film was “Bastard out of Carolina” (1996), the story of a southern girl abused by her father. It was initially made for TNT, but cable mogul Ted Turner rejected it because of some rather graphic scenes of molestation and child rape in the director’s cut. Showtime, the paid cable channel, eventually aired it, after it had grabbed the spotlight at the Cannes Film Festival. “I learned a tremendous amount,” she says of her directorial debut, “but there were hardships involved. I had hardly any preparation time and 28 shooting days — it was fast and furious.”

Huston’s second directing experience, “Agnes Browne”, based on Brendan O’Carroll’s bestseller “The Mammy”, “was harder yet” — she wound up acting in it, when comedienne and TV talk show host Rosie O’Donnell withdrew. “The film was well received overall,” she says, “but it wasn’t well-publicised. You work too much on something like that and put too much of your soul in to be happy.”

Although she is critical of her younger colleagues for being too aggressive and career-oriented, Huston acknowledges that “they seem really smart, more than we were” at their age. “They are focused and regimented. I couldn’t imagine being that myself. I thought I’d like to act because it’s lovely and glamorous; actresses are beautiful and get lots of attention.” She willingly names her favourites among the young generation of female stars — Kate Hudson, Angelina Jolie, Christina Ricci, Jena Malone, Reese Witherspoon — but cautions them against the “head-on, knock-out, drag-it-out fame” they experience at a very fragile age.

“It’s hard when you’ve saturated the public by the time you are in your early twenties — it doesn’t leave you a lot of room to move,” she says. “It’s dangerous because it wastes you, and unless you are really fortified and confident, and have your underpinnings neatly stacked underneath you, it would be very easy to lose your mind.”