DENZEL WASHINGTON

Washington Flair Ensemble

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

March 23, 2002

LOS ANGELES

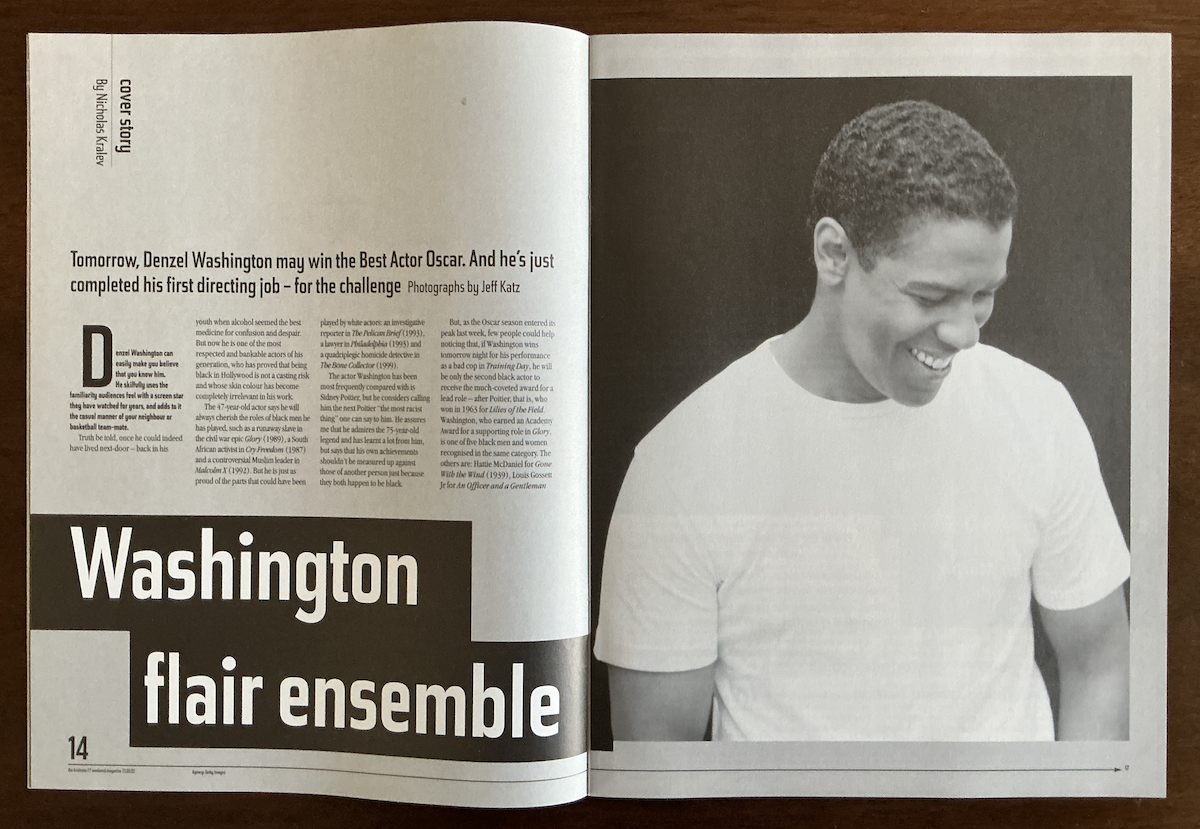

Denzel Washington can easily make you believe that you know him. He skillfully uses the familiarity audiences feel with a screen star they have watched for years, and adds to it the casual manner of your neighbour or basketball team-mate.

Truth be told, once he could indeed have lived next door — back in his youth when alcohol seemed the best medicine for confusion and despair. But now he is one of the most respected and bankable actors of his generation, who has proved that being black in Hollywood is not a casting risk and whose skin colour has become completely irrelevant in his work.

The 47-year-old actor says he will always cherish the roles of black men he has played, such as a runaway slave in the civil war epic “Glory” (1989), a South African activist in “Cry Freedom” (1987) and a controversial Muslim leader in “Malcolm X” (1992). But he is just as proud of the parts that could have been played by white actors: an investigative reporter in “The Pelican Brief” (1993), a lawyer in “Philadelphia” (1993) and a quadriplegic homicide detective in “The Bone Collector” (1999).

The actor Washington has been most frequently compared with is Sidney Poitier, but he considers calling him the next Poitier “the most racist thing” one can say to him. He assures me that he admires the 75-year-old legend and has learnt a lot from him, but says that his own achievements shouldn’t be measured up against those of another person just because they both happen to be black.

But as the Oscar season entered its peak this week, few people could help noticing that, if Washington wins Sunday night for his performance as a bad cop in “Training Day”, he will be only the second black actor to receive the much-coveted award for a lead role — after Poitier, that is, who won in 1963 for “Lilies of the Field”. Washington, who earned an Academy Award for a supporting role in “Glory”, is one of five black men and women recognised in the same category. The others are: Hattie McDaniel for “Gone With the Wind” (1939), Louis Gossett Jr for “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982), Whoopi Goldberg for “Ghost” (1990) and Cuba Gooding Jr for “Jerry Maguire” (1996).

Still fresh from his “Training Day” triumph, Washington stars as yet another man who could be “just anyone” — black or white — in his latest film, “John Q”, a drama about a working-class father whose primary school-age son has a heart three times the size of a normal one and urgently needs a transplant. But John’s health insurance doesn’t cover such an expensive procedure. The hospital refuses to put the boy’s name on the waiting list for a new heart unless the family comes up with $250,000. Determined to save his son’s life, whatever the consequences, John takes the emergency room hostage. “I could have put something there to make it a black issue,” Washington says, “but I didn’t.”

The movie, which co-stars Robert Duvall, James Woods, Anne Heche and Ray Liotta, received mixed reviews in the United States, though it topped the box office during its opening weekend last month, taking more than $23 million, and Washington’s performance won much praise. Most of the criticism was directed at the film’s “liberal” political message in support of national health insurance — an issue former the first lady Hillary Clinton put a lot of effort into, without resolving, back in 1993, when the script of “John Q” was written.

Washington says he “wasn’t attracted to the film because of the issue, but because of that family”. He still has his opinion: “I think the system has to be re-examined. Do I think that starting Monday we all go on national health insurance? No. But there has to be at least a back-up system for people who fall into the cracks.”

The press junket for “John Q” has just ended and we are talking in a suite at the Four Seasons hotel in Los Angeles. Washington, his co-stars and the director, Nick Cassavetes, have been rotating between six rooms, each with seven or eight journalists in it, discussing the film. The day before, the television networks did their five-minute interviews. Unlike most of his colleagues, who detest being subjected to the same questions, which they have to answer in a matter of seconds, Washington doesn’t complain: “I have to do junkets every so often for a couple of days. They pay us a lot of money to do what we do, and it’s called show business, so part of it is promoting the movie.”

As the 6-foot-tall actor, dressed in his signature tracksuit, T-shirt, sneakers and baseball cap, gives me a firm handshake and a megawatt smile, I mention that it had taken me much longer to arrange an interview with him than with Secretary of State Colin Powell, with whom I had set up a meeting the week before. Washington says he pays a publicist to deal with the media, but he is curious to hear about my experience with Powell’s State Department. Both men are on the board of the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and have met “a couple of times, though I can’t tell you I know him well. He grew up not too far from me in The Bronx. He obviously has a big hand in what’s going on”.

Washington, who thinks the Bush administration is handling the war on terrorism in the “right way”, says he has a “personal interest” in it, “having done ‘The Siege’ (1998), which talked about these very issues”. During the research for the film, which is about the secret abduction of a suspected terrorist that leads to a wave of terror attacks in New York and the declaration of martial law, the actor remembers noticing that communication both within the FBI and the CIA, as well between the two agencies, was rather weak. FBI agents complained to the crew that, because of limited resources, they were “catching one in three” terrorists.

Another reason for Washington’s interest in the anti-terrorism campaign is his extensive experience of playing soldiers — in the Civil War, the Second World War, the Cold War, as well as the conflicts in the Falklands and the Middle East — which has instilled in him great respect for the men and women and uniform. “I’ve done training with the military, both here and in Britain, and I remember calling everybody ‘brother’. I understand what that camaraderie is all about,” he says.

A focused and intense actor whose relaxed demeanour in real life gives way to a complex mixture of emotions onscreen, Washington, always open to “taking chances”, has just tried his hand at directing. His debut, a film at present known only as “The Untitled Antwone Fisher Story”, is based on an abandoned and abused black young man who turns his life around during his 11 years in the Navy, where he meets a psychiatrist, played by Washington. At first, Washington’s only involvement with the film was as an actor — he was offered the psychiatrist part about five years ago. But “the story was so powerful”, he says, that he felt it was the right project with which to step behind the camera.

“I found that I knew a lot more than I thought. One of the first things I learned was: get the best people and let them do their jobs. I was pleased that people were coming up to me saying, ‘You can do this’. I’m a good actor — I can at least act like a director. I’ve made 30 films in 20 years, so something has to rub off.”

Washington says he loves acting, but it doesn’t fully satisfy and challenge him. “The people who are reading this are probably thinking, ‘Is he crazy, with all the money they are paying him as an actor?’ But money doesn’t take care of everything.” He even tries to make it personal to me — maybe I’ll understand him better: “It’s like you are there at the State Department every day, and I’m sure it’s quite exciting, but sometimes you want to come out here. It’s not like I’ll make the big acting retirement announcement. I was just getting a little stale.

“I needed to fear a failure,” he says. “I’m the guy who is supposed to have answers to all questions. As an actor, I come in, do my thing, and I’m out of there. The director has to manage people, which I hadn’t had the practice for and which was invigorating and good for me to open up — like the captain of a ship, to let folks have their creative freedom, and yet still try to head in a certain direction.”

“Be specific” was one of the most important pieces of advice he gave the young actors who played the lead roles, Washington says. In one scene, in which Antwone and a girl were at dinner, “I thought it would be a nice touch if the girl — they didn’t have a lot of money — had one of those aluminium foiled doggy bags, and they stuffed the food in. You come into a room with a set of circumstances. In order to know where you are going, you have to know where you are coming from.”

For his part, Washington says he certainly knows his roots well. “I remember what it is not to have money and to have to sneak on the train, or to give the $1 to my wife that day and still sneak on. We were struggling actors,” recalls the man who has just signed on to play a police chief in a thriller called “Out of Time” for $20 million.

Washington was born on December 28, 1954, in Mount Vernon, a middle-class area he describes as a “buffer zone” between New York City and the wealthy Connecticut suburbs. He was named after his father, a Pentecostal minister who divorced his mother, Lynne, owner of several beauty shops, when Denzel was 14. Although a self-defined underachiever as a student, he won a scholarship to a boarding school in upstate New York and later enrolled at Fordham University in the Big Apple.

That was probably the darkest time in Washington’s life. Money shortages forced him to work odd jobs at the “post office and the sanitation department” in his college years. “I used to work the midnight shift at a record-pressing factory before college, and also worked in a barber’s shop.” He drank heavily and his entire life seemed to be in a mess. He couldn’t even decide what he wanted to study: “I started with biology, then did political science and journalism — I was trying to find myself, I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

But then, at a summer school, a friend convinced him to get on a stage and perform for the kids. Washington’s search was over. He switched to drama as soon as he returned to Fordham. After graduation, he went to the American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco and appeared on the New York stage, with such troupes as the New York Shakespeare Company and the Negro Ensemble Company. In 1981, having broken into television with two films and played a role in his first feature, “Carbon Copy”, Washington was on stage again, in Charles Fuller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “A Soldier’s Story”, a 1940s drama set in a Louisiana army camp in the wake of an unpopular black officer’s murder.

That performance was his ticket to big-league movie-making. The director Norman Jewison happened to be in the audience one night, and later cast Washington in the 1984 film version of the play. Shooting took place during the actor’s work on the TV medical series “St. Elsewhere”, but executive producer Bruce Paltrow, whose daughter Gwyneth was then only 10, was happy to give him time off. During the show’s six-year run, the rising star also played in “Power” (1986), with Richard Gere and Gene Hackman, and “Cry Freedom”, in which the role of South African activist Steve Biko brought Washington his first Oscar nomination.

Although his next two movies, “The Mighty Quinn”, in which he played a Caribbean island police chief, and “For Queen and Country”, about a Falklands veteran returning to civilian life, were financial disappointments, his third role in 1989, as Trip, the angry runaway slave who takes up arms against the confederacy in “Glory”, won him an Academy Award and placed him on Hollywood’s A-list. The brilliant supporting actor who easily stood out in a diverse cast was ready to become a name-above-the-title leading man.

But his next big break came five films and three years later, in “Malcolm X”, which earned him another Oscar nomination. In 1993, he played Don Pedro in “Much Ado About Nothing” and two of his most memorable roles: a homophobic but sympathetic lawyer opposite Tom Hanks in “Philadelphia” and an investigative reporter in “The Pelican Brief”, with Julia Roberts.

Along with a flourishing career, Washington’s personal life was becoming the envy of Hollywood. He has been happily married to actress and singer Pauletta Pearson for 19 years, and they have four children: John David, Katia and the twins Malcolm and Olivia. The year Washington’s youngest kids were born, 1991, he lost his father, with whom he hadn’t been very close but with whom he tried to compensate for lost chances as the end approached. “I got to know him better during the last several years of his life. You know how people say, ‘Once a man, twice a child’. When he became a child again, I became the father and took care of him.”

Washington continued his prolific work with “Crimson Tide” and “Virtuosity” in 1995, followed by “Courage Under Fire” and “The Preacher’s Wife” in 1996, as well as “Fallen”, “He Got Game” and “The Siege” in 1998. The next year, in addition to “The Bone Collector”, he also did “The Hurricane”, the story of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a boxer wrongly imprisoned for murder who is eventually proven innocent, for which he was again nominated for an Academy Award. “Sometimes there is a lot of pressure when you play a real-life character, especially if the person is still alive,” he says. “I imagine there was pressure on Will Smith [when he played] Ali.”

Smith is in direct Oscar competition with Washington, who has now been nominated five times. He doesn’t hide his excitement and says he never buys into the statements of fellow actors who claim that they care little about winning or losing.

“They are lying,” Washington is almost shouting by now. “That’s what you are supposed to say. At this point in my life, it’s good to be recognised. There is no greater accolade for an actor than winning the Academy Award — and there is nothing wrong with that. It’s not a life-changing experience, but it’s nice.”