RICHARD HOLBROOKE

So Busy at Diplomacy, He 'Ignored' the U.S. Election

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

January 6, 2001

NEW YORK

Richard Holbrooke is about to make yet another exit from the U.S. foreign policy stage — the fourth in his 38-year career. Many of the people who know him well, though, are already predicting a stormy comeback.

This is the second time he has come within a whisker of the job that many in Washington say he’s been pursuing for years: secretary of state. In 1996, a year after he brokered the Dayton agreements that ended the war in Bosnia, he lost out to Madeleine Albright — the first woman to hold the top diplomatic post.

This time, it was the slimmest of election wins by Republican George W. Bush that decided Holbrooke’s fate. Although the Democratic candidate, Al Gore, was careful during the campaign not to reveal his potential Cabinet choices, foreign policy insiders were betting that Holbrooke, at present U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, would most likely have been his choice to succeed Albright. Instead, Holbrooke, 59, is off to the Council on Foreign Relations, where many prominent figures find refuge after leaving high-level government jobs.

Looking forward, he says the broad outlines of the Bush administration’s foreign policy should be bipartisan, and “the work with Congress should be deep and intensive”. In an attempt to make the transition from the existing administration as smooth as possible, he met Colin Powell, nominated by Bush to be the next secretary of state.

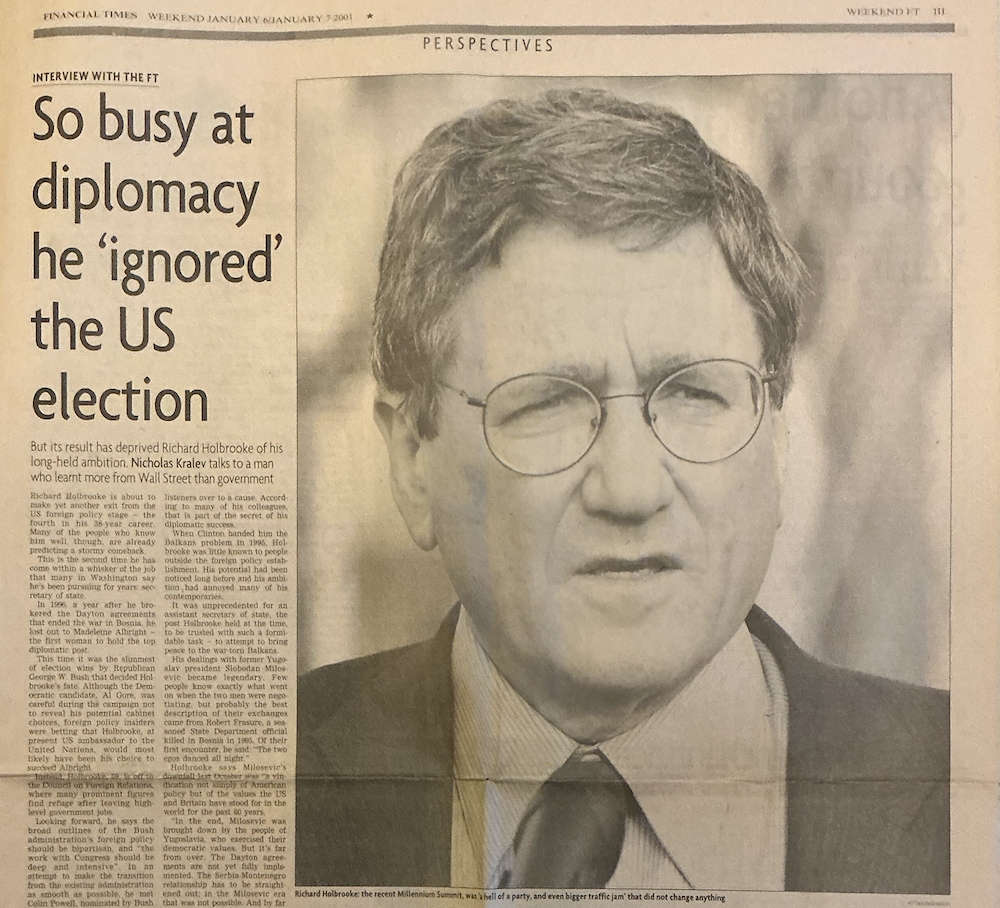

Visibly exhausted at the end of his nearly 18-month U.N. tenure, he makes a futile effort to sound as though other matters have passed him by. He assures me, for example, that he “ignored” the election, although he knew it was “out there”. We meet in his office at the U.S. mission to the United Nations in New York. Holbrooke, notorious for straight talking, which some say borders on arrogance, calls the recent Millennium Summit, held across the street from where we are sitting, “a hell of a party, and even bigger traffic jam” that did not change anything. “It was a combination of circus and serious purpose. The circus elements were what was visible to the naked eye, but the private meetings were useful.”

With a voice surprisingly soft and seductive for his imposing figure, Holbrooke utters every word in an almost theatrical manner, as if he’s trying to win listeners over to a cause. According to many of his colleagues, that is part of the secret of his diplomatic success.

When Clinton handed him the Balkans problem in 1995, Holbrooke was little known to people outside the foreign policy establishment. His potential had been noticed long before, and his ambition had annoyed many of his contemporaries. It was unprecedented for an assistant secretary of state, the post Holbrooke held at the time, to be trusted with such a formidable task: to attempt to bring peace to the war-torn Balkans.

His dealings with former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic became legendary. Few people know exactly what went on when the two men were negotiating, but probably the best description of their exchanges came from Robert Frasure, a seasoned State Department official killed in Bosnia in 1995. Of their first encounter, he said: “The two egos danced all night.” Holbrooke says Milosevic’s downfall last October was “a vindication not simply of American policy, but of the values the United States and Britain have stood for in the world for the past 60 years”.

“In the end, Milosevic was brought down by the people of Yugoslavia, who exercised their democratic values. But it’s far from over. The Dayton agreements are not yet fully implemented. The Serbia-Montenegro relationship has to be straightened out; in the Milosevic era that was not possible. And by far the most difficult issue — the future status of Kosovo — only now can we begin to address.”

Although Holbrooke, as well as other U.S. officials, has said that Milosevic, indicted by the war crimes tribunal, belongs in court in The Hague, he’s not sure “he will ever get there”. Five years after Dayton, Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb leaders also indicted by the tribunal, are still at large, he points out.

During his Balkans mission, Holbrooke revealed his most symptomatic professional characteristic: being his own boss. His views of how things should be done often differed from what officials in Washington instructed him to do. He took risks, relying on his intuition. Some foreign policy analysts say his determination to do things his own way, and his weakness as a team player, cost him the top State Department job in 1996.

Holbrooke entered the U.S. Foreign Service in 1962, after graduating from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Sensing where the action lay, he asked to go to Vietnam, where he started as an economic development officer, and later worked on the fruitless Paris peace talks. He left public service in 1969, but returned when Jimmy Carter was elected president in 1976 to become assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs. After Ronald Reagan won the White House in 1980, Holbrooke took a job at Lehman Brothers in his native New York, where he made a little fortune, and stepped up his social activities and networking.

He also became involved in refugee issues. His parents had been refugees from the regimes of Hitler and Stalin and he “started in Thailand in 1979, when almost a million refugees poured out of Cambodia”. He joined the board of the International Rescue Committee and was later chairman of the board of Refugees International.

Despite his hopes for a prominent post in 1993, he was offered the ambassadorship to Germany. After a year in Bonn, he was summoned back to Washington to become assistant secretary of state for European affairs. It was hard for him to return to the same pay level he had been on nearly 20 years earlier, but he took the job.

And then came the Balkans — the “problem from hell”, as then-Secretary of State Warren Christopher called it, of which no one was willing to take charge. That’s exactly why Holbrooke wanted it. After the success of Dayton and the limelight he seemed to enjoy, there weren’t many government jobs in which he was interested. He went back to investment banking — this time at Credit Suisse First Boston, again in New York. He says he learned a lot from Wall Street, rather than from government. “Government tends to be viewed by most people as a process, while Wall Street is not interested in process, but only in outcome. After all, government is about helping people, not just about maintaining its own processes. I also learned about the importance of closing a deal.”

He had too little time as U.N. ambassador to get through all of his ambitious agenda. But he still managed to dedicate his entire month as president of the Security Council to Africa — something not done before — and to convince Congress to pay part of the long-standing U.S. dues to the United Nations before Washington lost its vote in the General Assembly. Having called the United Nations “indispensable” to U.S. foreign policy, he says the only choice for the organisation now is to reform itself in order to be saved. “And the more reform, the more money will come,” he says simply.

Holbrooke reckons the “core issue” of U.S. foreign policy in the next several decades will be Washington’s relations with China. “Each cycle of history is marked by one great sweeping issue,” he says. “The first half of the 20th century was marked by the battle against fascism, the second half by the rise and fall of communism. “The large, overriding issue of the first half of the new century will be the relationship between the U.S. and China. But I don’t think it’ll be a struggle that one has to win and the other has to lose. It will be the search for co-existence, in a way in which each country respects the other.”

Looking back with a critical eye at Clinton’s foreign policy legacy, he says he was troubled by the fact that the U.S. intervened in Bosnia too late, and has “grave concerns about what happened in Rwanda”. No one has asked the United States to be a global cop, he says, but it presents itself as the world’s only superpower, and, while this does not mean that it should attempt to solve every problem, it does mean that it has certain responsibilities.

“If I had to sum up my greatest concern about American foreign policy today, it’s the gap between our rhetoric and our resources,” he says. “We keep proclaiming lofty goals, and then not putting up enough resources to achieve them.”