TED OLSON

Trying, Crying Times

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

May 11, 2002

WASHINGTON

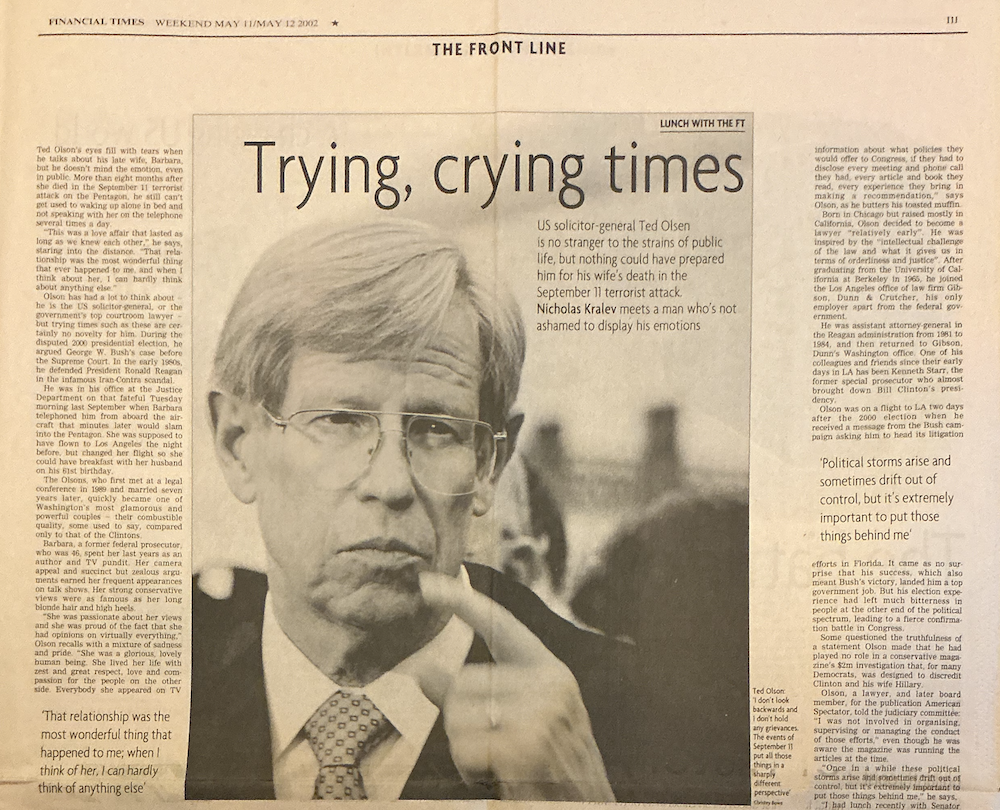

Ted Olson’s eyes fill with tears when he talks about his late wife, Barbara, but he doesn’t mind the emotion, even in public. More than eight months after she died in the September 11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon, he still can’t get used to waking up alone in bed and not speaking with her on the telephone several times a day.

“This was a love affair that lasted as long as we knew each other,” he says, staring into the distance. “That relationship was the most wonderful thing that ever happened to me, and when I think about her, I can hardly think about anything else.”

Olson has had a lot to think about — he is the U.S. solicitor-general, or the government’s top courtroom lawyer — but trying times such as these are certainly no novelty for him. During the disputed 2000 presidential election, he argued George W. Bush’s case before the Supreme Court. In the early 1980s, he defended President Ronald Reagan in the infamous Iran-Contra scandal.

He was in his office at the Justice Department on that fateful Tuesday morning last September, when Barbara telephoned him from aboard the aircraft that minutes later would slam into the Pentagon. She was supposed to have flown to Los Angeles the night before, but changed her flight so she could have breakfast with her husband on his 61st birthday.

The Olsons, who had met at a legal conference in 1989 and married seven years later, quickly became one of Washington’s most glamorous and powerful couples — their combustible quality, some used to say, compared only to that of the Clintons. Barbara, a former federal prosecutor, who was 46, spent her last years as an author and TV pundit. Her camera appeal and succinct but zealous arguments earned her frequent appearances on talk shows. Her strong conservative views were as famous as her long blond hair and high heels.

“She was passionate about her views, and she was proud of the fact that she had opinions on virtually everything,” Olson recalls with a mixture of sadness and pride. “She was a glorious, lovely human being. She lived her life with zest and great respect, love and compassion for the people on the other side. Everybody she appeared on TV against, as far as I know, loved jousting with her.”

I joined Olson at 7:30 a.m., and although my day had just begun, Olson had been up for three and a half hours, one of them at work. “I get up at 4 a.m., run on the treadmill and try to exercise — a person at my age needs to do that to stay somewhat reasonably fit,” he tells me as we wait for the restaurant to open. The exercise has apparently paid off: with his tall, slim figure, Olson looks at least five years younger than his 61 years. He is wearing a grey suit and his signature big-frame spectacles.

Olson had asked to meet somewhere close to the Justice Department, so I had chosen the Willard hotel, one of the oldest in Washington, only a couple of blocks from the White House. We are seated at a round table by the fireplace; the restaurant is furnished and decorated to suit the hotel’s Second French Empire Beaux-Arts architectural style. “I’ll have just an English muffin,” he tells the waiter, who has brought coffee and orange juice. After a quick look at the long menu, I see no point in reading it all, so I make the same modest order.

When we arranged to meet, I had promised not to talk about the painful subject of his wife’s death until after the breakfast, so we began by discussing his career. Mainly because of the tragedy, Olson became one of the Bush administration’s more visible spokesmen on anti-terrorism legislation, but he says his actual role in drafting the laws was relatively small.

“I participated somewhat in the deliberative process that led up to the legislation, and to a certain extent in urging Congress to adopt it and explaining to the American public.” In spite of the criticism that the administration — and especially Attorney General John Ashcroft — have sacrificed civil rights in the name of national security, Olson insists the legislation has “more than adequate assurances” to protect civil liberties. “There is judicial supervision and approval of many of the information-gathering activities and law-enforcement mechanisms that the legislation enacts,” he says. “In many, if not all, of those cases we have to go to judges for approval in advance, and judges watch over the implementation of those orders.”

Olson, considered one of the best constitutional lawyers in the United States, says he “respects the law and enjoys the study of the law” as much as he loves advocacy. He finds it a “great honour and personal inspiration to appear before the Supreme Court on behalf of the government”, and a “great excitement just to watch the court in action”. Representing the U.S. government and the particular administration he serves is “almost identical”, says Olson, whose office is involved in two-thirds of all lawsuits that reach the Supreme Court.

But he says that the White House has a “policy interest in 5 percent or less of the cases”. One such instance is an argument he is about to undertake indirectly related to the Enron scandal: defending vice-president Dick Cheney’s refusal to turn over to Congress documents and other information on all meetings he had while developing the administration’s energy policy.

“The president and vice president have taken a position that it will be an intrusion on their ability freely to gain information about what policies they would offer to Congress, if they had to disclose every meeting and phone call they had, every article and book they read, every experience they bring in making a recommendation,” says Olson, as he butters his toasted muffin.

Born in Chicago but raised mostly in California, Olson decided to become a lawyer “relatively early”. He was inspired by the “intellectual challenge of the law and what it gives us in terms of orderliness and justice”. After graduating from the University of California at Berkeley in 1965, he joined the Los Angeles office of law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, his only employer apart from the federal government.

He was assistant attorney general in the Reagan administration from 1981 to 1984, and then returned to Gibson, Dunn’s Washington office. One of his colleagues and friends since their early days in LA has been Kenneth Starr, the former special prosecutor who almost brought down Bill Clinton’s presidency.

Olson was on a flight to LA two days after the 2000 election when he received a message from the Bush campaign asking him to head its litigation efforts in Florida. It came as no surprise that his success, which also meant Bush’s victory, landed him a top government job. But his election experience had left much bitterness in people at the other end of the political spectrum, leading to a fierce confirmation battle in Congress.

Some questioned the truthfulness of a statement Olson made that he had played no role in a conservative magazine’s $2 million investigation that, for many Democrats, was designed to discredit Clinton and his wife Hillary. Olson, a lawyer, and later board member, for the publication American Spectator, told the Judiciary Committee: “I was not involved in organising, supervising or managing the conduct of those efforts,” even though he was aware the magazine was running the articles at the time.

“Once in a while these political storms arise and sometimes drift out of control, but it’s extremely important to put those things behind me,” he says. “I had lunch recently with Senator Patrick Leahy, the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, who voted against me, but we both know that it was very important to put all that behind us. I don’t look backward and I don’t hold any grievances. The events of September 11 put all those things in a sharply different perspective.”

He finds it much more difficult to move on in his personal life. “I hope that there are other people in the world you can have close relationships with,” he says. “I hope that some day that will happen to me again, but I have no expectations that it will be like my relationship with Barbara, because I can’t imagine trying to reproduce that. It wouldn’t be fair to me or the person I might have a relationship with.”