JAMES SPADER

Specs, Fame and Satisfaction

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

November 16, 2002

LOS ANGELES

James Spader calmly challenges the “mystery man” image he’s had among film audiences since playing a sexually troubled youth in “Sex, Lies and Videotape” (1989), and he does it with the simplest, facts-of-life arguments. His choice of roles, he explains, has never been determined by a need to “manage” his career or build himself up as a particular “type”, but rather by how a certain project fits into the rest of his life — sometimes it’s “my being out of money”, sometimes it’s “my children being out of school”. So he would “take whatever I can find at that time” and “try to make the best of it”.

“Every few years, I do a film I’m really excited about, and the rest of the time I’m finding a way to make a living, still doing something that interests me,” he says in a characteristically soft manner. “I’m able to do that, and it works out great for me. I like making films, but I’m not going to connect my entire life to it.”

As for the other part of the “mystery” — his absence from the mainstream Hollywood scene in the past decade despite the high expectations of some critics who saw him as “one of the 1990s most formidable leading men” — that’s a different story. He may not have mapped out his career path, but he says staying out of the public eye was a clear and conscious choice. He realised that “fame facilitates filmmaking”, but he wasn’t ready to accept giving up his privacy. “It’s a juggling act — I’m walking a fine line between keeping celebrity at bay and making successful films.”

Spader has, indeed, never stopped working, although many people have asked the question: “Where did he disappear?” Well, the truth is, most of Spader’s films have been modest, little-marketed projects — he has starred in more than 30 pictures in just over 20 years — and that’s exactly the kind of movie “Sex, Lies and Videotape” was. The difference is that you don’t hit the jackpot every day.

Time may have come, however, for another lucky break, in a role some are sure to find disturbing yet again: a sadomasochistic lawyer in the film “Secretary”. The art-house movie has enjoyed excellent reviews, including such pronouncements as “ground-breaking” and “a picture with heart”. Whatever the film’s effect on Spader’s career, he is being talked about more than he has been for years.

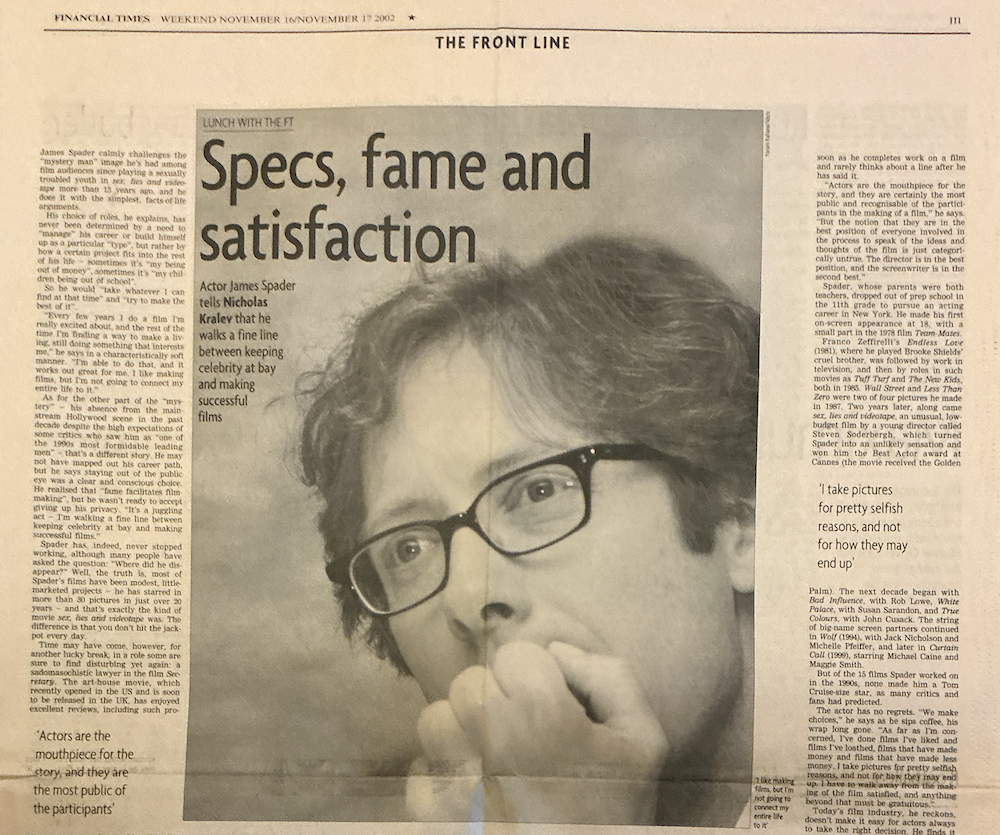

A rather young 42-year-old, with looks more typical of a heart-throb school teacher than a glamorous actor, Spader is already waiting outside one of the restaurants at the Beverly Hills hotel, now owned by Hilton and home of the Golden Globes and other award ceremonies, when I arrive. Smartly dressed in a dark blue jacket and a white shirt hanging out of black trousers, his spectacles are the final item to dispel the image of the tortured, amoral blond yuppies he portrayed in the late 1980s.

The small talk on our way to the table consists of remarks about the horrific Los Angeles traffic, the actor’s native Boston, where I’d lived for two years, and his two sons, Sebastian, 12, and Elijah, 9. We both agree that this is hardly the best place to dine in the glitzy Beverly Hills, but its location, at the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica Boulevards, beats most other choices.

As we take our seats, Spader mentions “Secretary”, visibly pleased with the interest the film has generated. “At the end of the day, it’s a love story,” he says, then gives me a brief plot summary: “I play a failing attorney, though his profession is really not central to who he is. Maggie Gyllenhaal plays a woman who has just stayed at a mental institution and is looking for employment. She answers an ad for a new secretary in my law firm and I hire her. We both discover that we have active, yet secret, lives as sadomasochists. I have already been acting it out with partners in my life, but she never has before. We start a relationship and end up falling in love. The tone of the movie is funny, sweet and romantic. I think it’s a lovely little film.”

He finally opens the menu and, after a quick scan, chooses a chicken wrap. I go for the rich lunch buffet. Later, when his plate arrives, Spader wastes no time, biting at the wrap in the pause between two sentences. “Sorry the conversation will be mingled with me munching,” he apologises. “I have to find a way to eat this thing,” he says as the wrap seems to unravel in his hands. “Look at this, the entire thing fell apart. I have to attack it from a different perspective, I guess.”

I share my impression from the little written about him in the press that he is not very keen on speaking on behalf of his characters. He says he has “never been reticent talking about a character”, but admits that “it’s not the easiest thing to articulate very eloquently, and I’m not always sure I’m in an objective position to be able to reflect on people I’ve played”. He adds that he rids himself of his character as soon as he completes work on a film and rarely thinks about a line after he has said it.

“Actors are the mouthpiece for the story, and they are certainly the most public and recognisable of the participants in the making of a film,” he says. “But the notion that they are in the best position of everyone involved in the process to speak of the ideas and thoughts of the film is just categorically untrue. The director is in the best position, and the screen writer is in the second best.”

Spader, whose parents were both teachers, dropped out of prep school in the 11th grade to pursue an acting career in New York. He made his first on-screen appearance at 18, with a small part in the 1978 film “Team-Mates”. Franco Zeffirelli’s “Endless Love” (1981), where he played Brooke Shields’ cruel brother, was followed by work in television, and then by roles in such movies as “Tuff Turf” and “The New Kids”, both in 1985. “Wall Street” and “Less Than Zero” were two of four pictures he made in 1987. Two years later, along came “Sex, Lies and Videotape”, an unusual, low-budget film by a young director called Steven Soderbergh, which turned Spader into an unlikely sensation and won him the Best Actor award at Cannes (the movie received the Golden Palm).

The next decade began with “Bad Influence”, with Rob Lowe, “White Palace”, with Susan Sarandon, and “True Colours”, with John Cusack. The string of big-name screen partners continued in “Wolf” (1994), with Jack Nicholson and Michelle Pfeiffer, and later in “Curtain Call” (1999), starring Michael Caine and Maggie Smith. But of the 15 films Spader worked on in the 1990s, none made him a Tom Cruise-size star, as many critics and fans had predicted.

The actor has no regrets. “We make choices,” he says as he sips coffee, his wrap long gone. “As far as I’m concerned, I’ve done films I’ve liked and films I’ve loathed, films that have made money and films that have made less money. I take pictures for pretty selfish reasons, and not for how they may end up. I have to walk away from the making of the film satisfied, and anything beyond that must be gratuitous.”

Today’s film industry, he reckons, doesn’t make it easy for actors always to take the right decision. He finds it unrealistic for investors “to want guarantees in a business where there are no financial guarantees”. They try to cover their “bets most efficiently, and that breeds awful filmmaking, because it doesn’t call for originality but repetition of previous success — preferably as close of a replica as possible”.

“So,” he muses, “I don’t think any actor, no matter who they are — even if they have all the choices in the world, even if every script that comes along is sent to them first — is able to have a fulfilling and satisfying film again and again. That’s just not the way it works.”