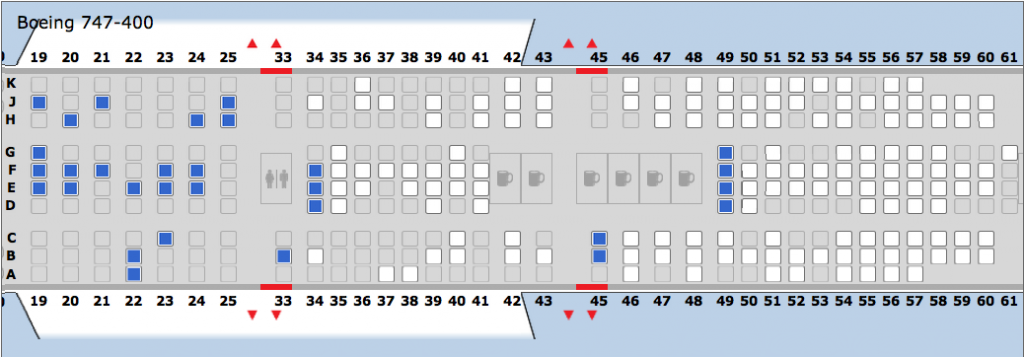

The post-departure seat map in First and Business Class of UA863 from SFO to SYD on June 19, 2012 (courtesy of united.com).

Even as most flights are packed these days, some planes still take off with plenty of vacant seats, including in First and Business Class, effectively losing the airlines hundreds of thousands of dollars. Offering lower last-minute fares on undersold flights seems a logical solution, and carriers do it sometimes, but those attempts are utterly insufficient.

Let’s look at a recent international flight — most U.S. airlines give away free upgrades on domestic routes to fill their premium cabins. I picked a United Airlines flight on a route with traditionally heavy demand in Business Class: San Francisco to Sydney. As the above image shows, on June 19, that Boeing 747 left with 18 empty seats in Business Class, including on the upper deck. The snapshot was taken a day after departure, so the seat map presents an accurate picture. It’s worth noting that there were several non-revenue passengers on the flight, but I’ll ignore that fact in my analysis.

The lowest Business Class fare on United on that route is — and has been for some time — about $6,400, which requires a 50-day advance purchase. If bought at least 21 days before departure, a ticket costs about $9,800, and about $12,300 at least three days in advance. The lowest last-minute fare is about $12,800. You do the math to figure out how much money United lost as a result of those 18 unsold seats.

The airlines have supposedly sophisticated systems to handle such scenarios and maximize yields, but there surely is something wrong with the above picture. Is it possible some ticketed passengers missed their connection? Of course, but it’s unlikely that 18 people did.

What if United had lowered the fare to $4,000 or even $3,000? It would have made tens of thousands more. I realize there is no guarantee it would have sold all vacant seats at those prices, either, but with proper advertising, it would have likely sold at least several. While United offers the only nonstop service between San Francisco and Sydney, much of that revenue comes from connecting traffic. The other three airlines flying from the U.S. mainland to Australia — Qantas, Delta and Virgin Australia — offer the same fares as United, so United’s competitive advantage would have been obvious. With equal fares, many business travelers on that route prefer Qantas for better service.

The June 19 flight was by no means an exception. I’ve been watching that route for several months while helping clients flying it, and this has been a pattern. It’s true that those planes are full on certain days of the week, but mid-week flights have consistently taken off with quite a few vacant seats. United’s flights from Los Angeles to Sydney have fared a bit better — guess what, fares on that route are actually lower by about $1,000.

Economy Class has done worse than Business, as the image below indicates. Coach fares are much lower — certainly over $1,000 — but the empty seats are many more. Just a couple of hundred dollars less might have made a difference. United files discounted last-minute weekended coach fares domestically, but not internationally.

The post-departure seat map in Economy Class of UA863 from SFO to SYD on June 19, 2012 (courtesy of united.com).

So why doesn’t United lower those fares? Perhaps it doesn’t care — if the return flight was full, the plane had to go to Sydney to pick up all those passengers. Even so, it’s hard to see how additional revenue of tens of thousands of dollars would be something immaterial to any company. United and other carriers now offer paid upgrades — or “buy-ups” — at check-in, but apparently those weren’t enticing enough to fill more seats on June 19.

My impression is that United and most other airlines simply don’t have enough people working in inventory and revenue management to monitor flight loads and propose adjustments where necessary. There are millions of flights in a large carrier’s system at any given time. For the most part, until just a few days before departure, airlines rely on computer models and robots to manage flight inventory. Having human beings keep track of at least high-revenue routes for several weeks before departure would make a lot of sense. Sure, hiring new employees means higher labor costs, but the additional revenue would be much greater.

There is something else. United limits the use of system-wide — or global — upgrade certificates to coach tickets booked in W class or higher, and Business Class tickets booked in D class or higher. It has refused to remove that restriction despite repeated calls from numerous top-elite fliers. Delta’s rules are even more draconian, though American allows such upgrades on all fares.

But why can’t United exempt from that rule last-minute upgrades that can be requested only at check-in — just like it offers paid upgrades? On that June 19 flight, there were probably passengers on fares lower than W who wanted to use a system-wide certificate but weren’t allowed — at the same time, 18 Business Class seats remained vacant.

How would have that made United any money? Letting customers use upgrade certificates they have earned with their loyalty goes a long way. Even though no extra cash would have ended up in the carrier’s pocket for that particular flight, used certificates reduce the airline’s liability for accounting purposes. More importantly, such a gesture would have likely preserved and possibly expanded those customers’ loyalty, meaning they would have spent more money on United in the future.

I realize arguments that have to do with loyalty carry little weight with United’s current management, but in this case, the company would lose absolutely nothing.

Related stories:

Did United choose the best rez system?

American tries to entice top United fliers

United, Continental execs at odds over loyalty program

Airlines cut back on first-class service

What to do with empty premium seats?

2 comments