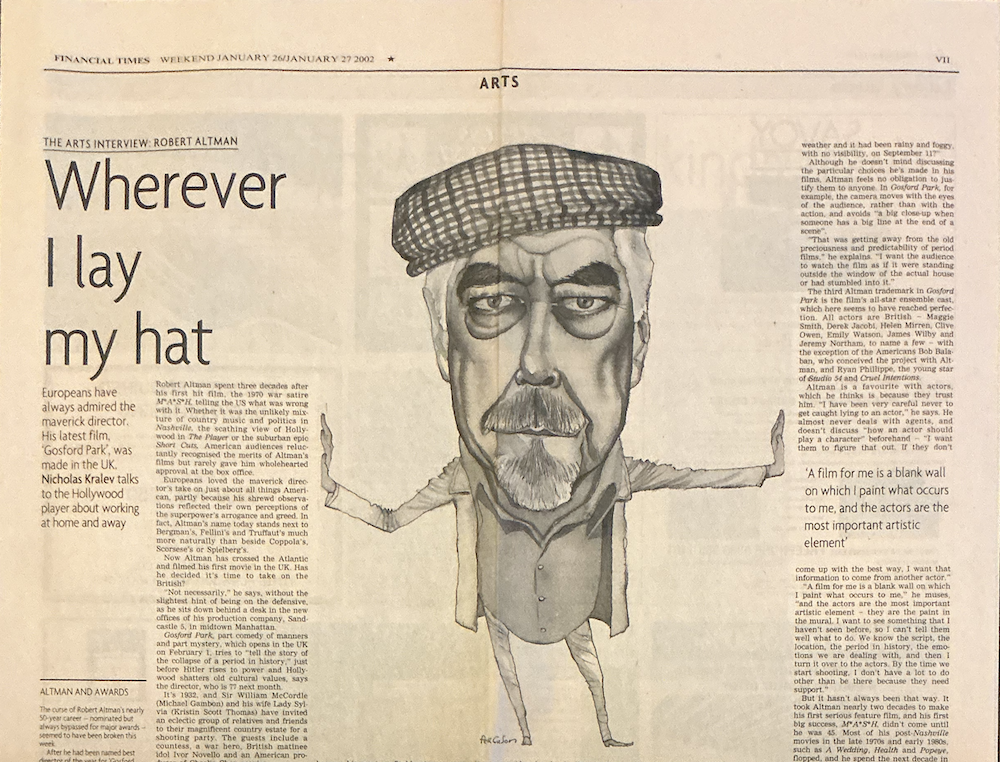

ROBERT ALTMAN

Wherever I Lay My Hat

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times

January 26, 2002

NEW YORK

Robert Altman spent three decades after his first hit film, the 1970 war satire “MASH”, telling the United States what was wrong with it. Whether it was the unlikely mixture of country music and politics in “Nashville”, the scathing view of Hollywood in “The Player” or the suburban epic “Short Cuts”, American audiences reluctantly recognised the merits of Altman’s films, but rarely gave him wholehearted approval at the box office.

Europeans loved the maverick director’s take on just about all things American, partly because his shrewd observations reflected their own perceptions of the superpower’s arrogance and greed. In fact, Altman’s name today stands next to Bergman’s, Fellini’s and Truffaut’s much more naturally than beside Coppola’s, Scorsese’s or Spielberg’s.

Now Altman has crossed the Atlantic and filmed his first movie in Britain. Has he decided it’s time to take on the British? “Not necessarily,” he says, without the slightest hint of being on the defensive, as he sits down behind a desk in the new offices of his production company, Sandcastle 5, in midtown Manhattan.

“Gosford Park”, part comedy of manners and part mystery, tries to “tell the story of the collapse of a period in history,” just before Adolf Hitler rises to power and Hollywood shatters old cultural values, says the director. It’s 1932, and Sir William McCordle (Michael Gambon) and his wife, Lady Sylvia (Kristin Scott Thomas), have invited an eclectic group of relatives and friends to their magnificent country estate for a shooting party. The guests include a countess, a war hero, British matinee idol Ivor Novello and an American producer of Charlie Chan movies. While they make themselves comfortable in the gilded drawing rooms “above stairs”, their personal maids and valets join the ranks of the staff “below stairs” — it’s through the servants’ eyes, rather than their masters’, that Altman and screenwriter Julian Fellowes tell the story, which culminates in a double murder.

Altman, who didn’t have a whodunit picture in his collection before “Gosford Park”, describes the plot as “Ten Little Indians” meets “The Rules of the Game”, referring to the 1939 Agatha Christie book originally titled “Ten Little Niggers” and made as a film called “Ten Little Indians” in 1966, and the 1939 Jean Renoir film-expose of the French social classes. But all similarities with those two genres stop there. “It’s not who done it, but who cares who done it,” says Altman. “It was the end of an era and what interested me were the social changes.” “Gosford Park” is undoubtedly his best work to date, Altman says. “I knew when we were doing it that it would be good. But I didn’t know if it would be received well.”

The film has enjoyed rave reviews in the United States and has done extremely well at the box office since it opened nationwide earlier this month. It has the potential to become his most profitable picture, says the director, who adds that he cares about money only in that it will help him finance his next project. “Gosford Park” masterfully brings together all the unique Altman concepts and techniques. The first of these trademark features is the way Altman uses the genre and the story. He says he’s not that interested in the story, because for him it’s just the base on which he builds his own castle.

“I don’t have to worry about the story, because you already know it,” he says of the murder mystery line in “Gosford Park”. “I’m not introducing a new philosophy to you, so you can be comfortable. I’m using those muscles in your memory that know what these films are. But then,” he pauses matter-of-factly, “I can turn around and say, ‘Maybe it’s not the way you think.’ That’s fun to me, and fun is really the only word I know. I like to upset the applecart along the way, but not the whole applecart — I’m not a revolutionary.”

A perfect example of challenging widely accepted images and ideas was Altman’s way of making a Western. Just before the filming of “McCabe and Mrs Miller”, the 1971 picture that failed to attract much interest when it opened but is now considered a classic, Warner Bros. “sent us a huge wardrobe with big cowboy hats”. When Altman questioned the common perception that “people wore those hats” two centuries ago, the studio said archive photos proved that they did.

“But a photographer didn’t run around snapping everybody’s picture back then,” Altman argues. “He was probably sitting in his room and some kid comes in and says, ‘Hey, get your camera! Some guy just came in town wearing the biggest hat you’ve ever seen.’ So he goes out and says, ‘Hold still, partner’, and takes his picture. That photo survives and now the research person at Warner Bros. says, ‘See, this is the kind of hats they wore.’ They didn’t take pictures of the kind of hats they wore, because they weren’t interesting.”

Another Altman artistic conviction successfully defended in “Gosford Park” is using the background — the sound and the weather — as realistically as possible. Since “Nashville” (1975), this has become an organic element of the non-linear, multi-layered and overlapping composition of many of his films, most notably “Short Cuts” (1993), which had 22 characters and nine story lines spread across the suburban grid of Los Angeles. In “Gosford Park”, there are 40 characters and 24 story strands.

Altman’s realism, as expressed in the dialogue of his films, once cost him his job. He had finished shooting “Countdown” in 1967 when studio boss Jack Warner decided to take a look at his footage. “That fool has got actors talking at the same time,” the 75-year-old tycoon burst in rage. The director was not allowed back to work the next day. His use of the weather hasn’t been nearly as disastrous, though he has already been asked why the sun — and not the rain — comes out after the murder in “Gosford Park”. “I don’t think the weather has any concern about what we are doing — it’s something we deal with every day,” he says. “Wouldn’t it have been great if they had reversed the weather and it had been rainy and foggy, with no visibility, on September 11?”

Although he doesn’t mind discussing the particular choices he’s made in his films, Altman feels no obligation to justify them to anyone. In “Gosford Park”, for example, the camera moves with the eyes of the audience, rather than with the action, and avoids “a big close-up when someone has a big line at the end of a scene”. “That was getting away from the old preciousness and predictability of period films,” he explains. “I want the audience to watch the film as if it were standing outside the window of the actual house or had stumbled into it.”

The third Altman trademark in “Gosford Park” is the film’s all-star ensemble cast, which here seems to have reached perfection. All actors are British — Maggie Smith, Derek Jacobi, Helen Mirren, Clive Owen, Emily Watson, James Wilby and Jeremy Northam, to name a few — with the exception of the Americans Bob Balaban, who conceived the project with Altman, and Ryan Phillippe, the young star of “Studio 54” and “Cruel Intentions”.

Altman is a favourite with actors, which he thinks is because they trust him. “I have been very careful never to get caught lying to an actor,” he says. He almost never deals with agents, and doesn’t discuss “how an actor should play a character” beforehand — “I want them to figure that out. If they don’t come up with the best way, I want that information to come from another actor.

“A film for me is a blank wall on which I paint what occurs to me,” he muses, “and the actors are the most important artistic element — they are the paint in the mural. I want to see something that I haven’t seen before, so I can’t tell them well what to do. We know the script, the location, the period in history, the emotions we are dealing with, and then I turn it over to the actors. By the time we start shooting, I don’t have a lot to do, other than be there, because they need support.”

But it hasn’t always been that way. It took Altman nearly two decades to make his first serious feature film, and his first big success, “MASH”, didn’t come until he was 45. Most of his post-“Nashville” movies in the late 1970s and early 1980s, such as “A Wedding, Health and Popeye”, flopped, and he spent the next decade in France and doing theatre in New York. “The Player”, a cynical story of a Hollywood executive (Tim Robbins) who murders a screenwriter and wins his girlfriend, was Altman’s triumphant comeback. Since then, in addition to “Short Cuts”, he has made “Prêt-a-Porter”, with another all-star cast led by Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, as well as “Kansas City”, “The Gingerbread Man”, “Cookie’s Fortune” and “Dr T & the Women”.

But how did a Kansas City boy go on to become this most idiosyncratic of American directors? “I suppose it came out of greed and ambition,” Altman admits. “I wanted to be accepted and admired.” When early success eluded him, Altman tried to find his own style, rather than imitate other celebrated American directors of his generation — Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, for instance.

“I’ve always been inside the bubble and I’m not aware of what goes on outside,” he says. “I can’t be a philosopher — I just do things from moment to moment. I always have this image that life is a river that keeps moving, and in it some people are swimming against the current, others with the current, and some change direction, but they are always moving. We try to hold on to where we were, and we can never be where we were.”