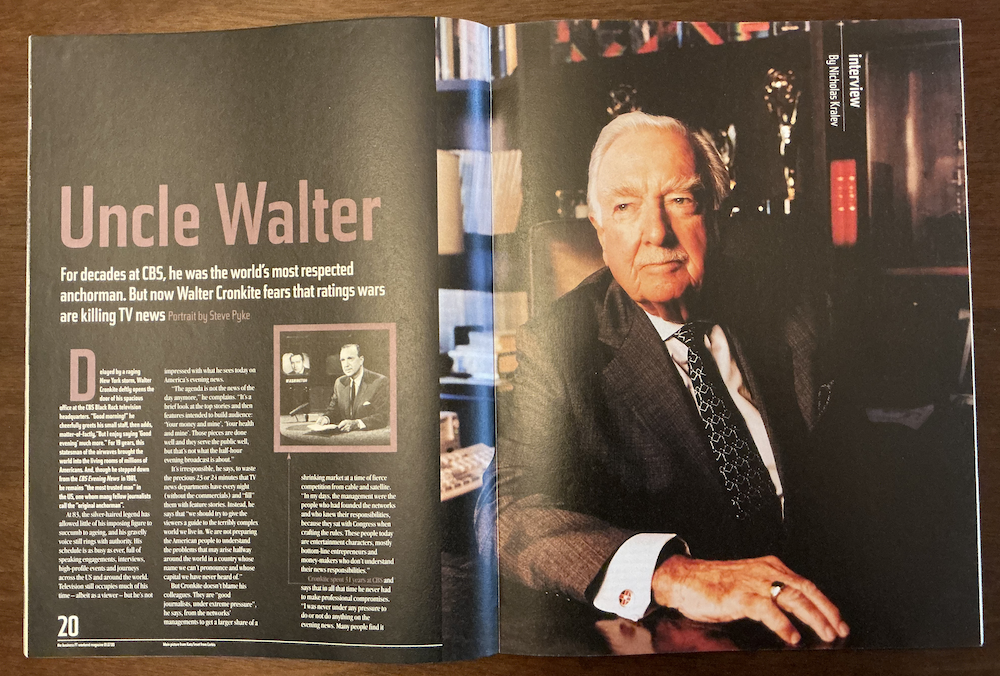

WALTER CRONKITE

Uncle Walter

By Nicholas Kralev

The Financial Times Magazine

July 1, 2000

NEW YORK

Delayed by a raging New York storm, Walter Cronkite deftly opens the door of his spacious office at the CBS Black Rock television headquarters. “Good morning!” he cheerfully greets his small staff, then adds matter-of-factly, “But I enjoy saying ‘Good evening’ much more.”

For 19 years, this statesman of the airwaves brought the world into the living rooms of millions of Americans. And though he stepped down from the “CBS Evening News” in 1981, he remains “the most trusted man” in the America, one whom many fellow journalists call the “original anchorman”.

At 83, the silver-haired legend has allowed little of his imposing figure to succumb to ageing, and his gravelly voice still rings with authority. His schedule is as busy as ever, full of speaking engagements, interviews, high-profile events and journeys across the United States and around the world. Television still occupies much of his time — albeit as a viewer — but he’s not impressed with what he sees today on America’s evening news.

“The agenda is not the news of the day anymore,” he complains. “It’s a brief look at the top stories and then features intended to build audience: ‘Your money and mine’, ‘Your health and mine’. Those pieces are done well and they serve the public well, but that’s not what the half-hour evening broadcast is about.”

It’s irresponsible, he says, to waste the precious 23 or 24 minutes that TV news departments have every night (without the commercials) and “fill” them with feature stories. Instead, he says, “we should try to give the viewers a guide to the terribly complex world we live in. We are not preparing the American people to understand the problems that may arise halfway around the world, in a country whose name we can’t pronounce and whose capital we have never heard of.”

But Cronkite doesn’t blame his colleagues. They are “good journalists, under extreme pressure”, he says, from the networks’ managements to get a larger share of a shrinking market at a time of fierce competition from cable and satellite. “In my days, the management were the people who had founded the networks and who knew their responsibilities, because they sat with Congress when crafting the rules. These people today are entertainment characters, mostly bottom-line entrepreneurs and money-makers who don’t understand their news responsibilities.”

Cronkite spent 31 years at CBS and says that, in all that time, he never had to make professional compromises. “I was never under any pressure to do or not do anything on the evening news. Many people find it hard to believe, but there were no commercial pressures, either.”

In a career that spanned nearly five decades, Cronkite covered all of the stories that defined an era: from the Second World War and the Nuremberg trials to the Korean and Vietnam Wars, from Queen Elizabeth’s coronation to John F. Kennedy’s assassination. But for his fellow Americans, he is much more than a famous journalist. In a 1972 poll on the public’s degree of trust in prominent figures, Cronkite was substantially ahead of then-president Richard Nixon and former vice-president Hubert Humphrey. For most of his time as an anchor, he kept the “CBS Evening News” at the top of the ratings, capturing the lion’s share of the 50 million viewers estimated to have been watching network news on any given evening. The trust was accompanied by a certain intimacy that comes from having a face and voice in your living room every night. Many people, not just his colleagues, used to call Cronkite simply “Walter” or “Uncle Walter”, while they usually addressed the NBC, and later ABC, anchorman David Brinkley as Mr Brinkley.

His former colleagues have said that the reason for Cronkite’s popularity and the deep respect he inspired was his “obsessive idea of personal responsibility for the world”. “People know that Walter Cronkite would never lie to them,” one of Cronkite’s former writers said in a 1981 newspaper interview. “Walter has an almost messianic turn of mind. He feels so much responsibility; he feels that if he doesn’t get it right, nobody else will.”

Now critical of television’s “infotainment” syndrome that blurs the lines between news and entertainment, in his days Cronkite strove to establish high journalistic standards in the newsroom. Since for years previously television had had actors, rather than journalists, reading the news, when he took over the “CBS Evening News” in 1962, he gave himself the title of managing editor to dispel the notion that he was a reader and his news a “show”.

One of his biggest challenges — valid even more today — was mixing facts and commentary in news reports. The problem stems from the “shortness given to reporters to handle a complicated subject”, he says. “They work laboriously to encompass all major issues, the pros and cons. But they become desperate to make it understandable, so they sum it up in a sentence, and then opinion creeps in. We were constantly cutting off the last sentences, simply because they were opinions, though not intentional.” But he’s quick to acknowledge the “place of commentary” on television, as long as it doesn’t “cross over to the newsroom”.

When he began in television, it was not as seriously regarded as the print medium. He set about establishing the standards of U.S. broadcast journalism. Now he says that “the book of standards” has not been amended, but in practice there has been “quite a loosening”. It comes from running after high ratings and trying to beat the competition, sometimes regardless of the means.

He admits that today’s “wash of information” is often overwhelming, while acknowledging the competition among the media. He finds that, currently, one of the biggest problems of print journalism is that many U.S. cities now have only one newspaper. “I don’t know how an editor of a monopoly newspaper knows how well, or how poorly, their staff are doing,” Cronkite says. He recalls his own time as a print reporter, when “copy boys” stood by at the loading dock of the competing newspaper, grabbed a copy of the latest edition as soon as it came out and rushed it into the newsroom, so that their editors could see what their own paper had missed.

No matter in what kind of medium you work, Cronkite says, ethics in journalism are most important — “the necessity to be fair and accurate, and to present the arguments of all sides on an issue. Beyond that, it’s all technique — how to write it or present it.” Equally, he rejects the idea that journalism is a real “subject”, worth teaching in college. There is a school named after him, the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Telecommunication at Arizona State University in Phoenix; he has tried to direct it more towards post-graduate studies: “I think it’s a shame for people to spend time in journalism courses in their undergraduate years. There’s so little time to get that general, classical education, which should occupy students in the first four years; then you can take journalism courses.”

Cronkite never went to journalism school. In fact, he never finished college; he dropped out of the University of Texas after his second year to work for the Hearst News Service, and then the Houston Press, when he was 19.

Born on November 4, 1916, in the week Woodrow Wilson was elected president, Cronkite says that he had his first “newsman” experience at the age of 6, when he went running down the hill through his Kansas City neighbourhood to spread the news of President Warren Harding’s death.

After secretly imitating radio sports broadcasters for years, at 21, Cronkite finally became one himself. He worked at two radio stations — in Kansas City and Oklahoma City — before joining United Press as a reporter in 1939. Then the war came, and Cronkite, summoned for the first time to the wire service’s foreign desk in New York, was sent to London. He has said that the war years were some of his happiest, and that he could leave behind the money and fame and go back to being a “hack reporter”.

When he covered Vietnam more than 20 years later, Cronkite was much more than a reporter; he was an institution. In 1968, he concluded a special report for CBS from the war zone with the words, “It is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out will be to negotiate, not as victors but as an honourable people.” At the White House, President Lyndon Johnson was reported to have said: “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.”

Cronkite liked covering political campaigns and conventions — he did dozens while at CBS — but had to limit his appearances on the campaign trail because he often overshadowed the candidates, who complained to CBS management that voters were distracted by the famous man’s presence. He says that this year’s presidential campaign has so far been “good and exciting, in the sense that issues are being discussed, though negative advertising has clouded considerably intellectual discussion”.

With all he has done for CBS, Cronkite says he still feels very bitter about the way he was treated after he left the “Evening News” in 1981: “I was promised to do coverage of special events, politics and national affairs.” But CBS’s interest rapidly vanished. “I felt let down by that.” In addition to the title of special correspondent, he was given a seat on the CBS board of directors and an annual salary of $1 million. Under the exclusive engagement, however, after seven years he would be a $150,000 consultant.

Cronkite has publicly criticised the mania among media executives to offer six-figure salaries to their stars (he does not exclude himself), thus creating a journalism elite that fails to understand the concerns of ordinary people. In fact, many of his comments and actions since he relinquished the chair at CBS have sparked controversy. Just three days after his last programme, he joined the board of Pan American World Airways. He was to be paid $10,000 a year, plus $300 for each board meeting he attended, and he and his wife could travel on Pan Am for free. Six months later, after a heated debate on whether journalists should be allowed to serve on corporate boards engulfed all the leading news organisations, Cronkite quit his directorship.

Last year, he agreed to be the narrator of the three-part BBC/TLC series “Tobacco Wars”, which critics called “the most thorough denunciation ever shown on TV of the steamy business of selling cigarettes”. For many, Cronkite’s voice was a reminder of the time when tobacco companies were huge television sponsors and TV hosts smoked on air. But for Cronkite, the fact “that we stopped people smoking in the U.S. is the media’s best accomplishment”.

He says he liked “The Insider”, the Oscar-nominated film about the tobacco industry’s whistleblower, Jeffrey Wigand. “It was much closer to the truth than those infotainment docudramas. I hate that form; it’s so dangerous. Oliver Stone’s “JFK” — a disastrous movie. Telling a whole generation that doesn’t know anything about President Kennedy’s assassination by filling their minds with those conspiracies that will never prove true — it’s terrible.”

The image of Cronkite announcing the death of Kennedy, with tears coming to his eyes, is the first that comes to the minds of most Americans when they hear the anchorman’s name. Cronkite has known every president since Herbert Hoover, including those who came after his glory days. A week after Bill Clinton confessed his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, he, along with wife Hillary and daughter Chelsea, joined Cronkite aboard his 60-foot ketch, Wyntje. “Bill Clinton is a great compromiser,” Cronkite says. “He’s very intellectual, and he understands issues very quickly with very little study, because he listens to experts, and as a consequence, he’s not stuck with the decisions that come up first. The economic success of the U.S. has made a major difference in his public acceptance.”

Having seen and experienced a lot in his long and dynamic life, Cronkite says his dominant concern today is peace. “It saddens me that we human beings are so capable in every other way except in managing our own affairs. What is it? Why can’t the Irish be sensible enough, for heaven’s sake, to achieve peace? This baffles me, and I personally believe in a world of federalism. We must establish a system of international law in which we can bring the perpetrators in our peaceful pursuits to justice. That’s essential to our future hopes. So I live with that. Selfishness and greed keep us from finding easy solutions to problems.”

But as much as he has been dedicated to his profession all his life, Cronkite always had “a certain imperative to be involved in what other people think are dangerous sports”. He learned to fly and for a long time raced automobiles. “I want to experience things,” he says. “I want to know personally what it’s like to do everything. I think that makes me a better journalist, because it exemplifies curiosity. I find it interesting, but my wife is driven crazy by it.”

Betsy, his wife of 60 years, is used to her husband’s peculiarities. Unlike most men, Cronkite will spend much more time in a shoe store than her, asking the shop assistants: “How in the world do you keep an inventory of all sizes, shapes and colours? You have a little store; where are all those shoes — in the back somewhere?” Another time, while sitting in a restaurant, he asked the waiters: “How on earth do you know what to buy each day? What happens to the food you don’t sell?”

He has other little fascinations that he values as much as the big ones. Of all expensive gifts and other memorabilia in his office, including Churchill’s bust, his favourite is a dinosaur model, which was given to him when he did a story about dinosaurs years ago. He also likes the old-fashioned radio his colleagues gave him when he stepped down from the “Evening News”. “Recognition from peers is important,” he says, much more so than the numerous awards that cover most of his shelves.

“I can’t help but be grateful for the awards,” he says, “but I’m afraid that most of them are meaningless.”